Contrition, Confession, and Candor

Lent 5B

For Sunday April 2, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Jeremiah 31:31–34

Psalm 51:1–12, or Psalm 119:9–16

Hebrews 5:5–10

John 12:20–33

|

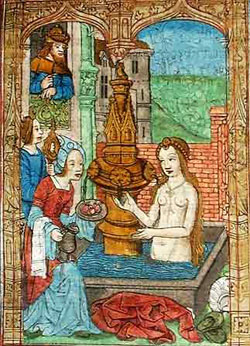

David and Bathsheba, Book of Hours (Paris, 1500). |

Confounding expectations of normal human behavior, one of the most eloquent expressions of human contrition comes from the most powerful statesman in Israel's history. An editorial gloss to the music director tells us that Psalm 51 is a song written by King David when the prophet Nathan came to him after he had committed adultery with Bathsheba. The editor does not mention that David also sent Bathsheba's husband Uriah to the front lines of battle to insure that he would be slaughtered and that Bathsheba would become his (see 2 Samuel 11 and 12).

Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your unfailing love;

according to your great compassion

blot out my transgressions.

Wash away all my iniquity

and cleanse me from my sin.For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is always before me.

Against you, you only, have I sinned

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you are proved right when you speak

and justified when you judge.

Surely I have been a sinner from birth,

sinful from the time my mother conceived me.

Surely you desire truth in the inner parts;

you teach me wisdom in the inmost place.Cleanse me with hyssop, and I will be clean;

wash me, and I will be whiter than snow.

Let me hear joy and gladness;

let the bones you have crushed rejoice.

Hide your face from my sins

and blot out all my iniquity.Create in me a pure heart, O God,

and renew a steadfast spirit within me.

Do not caste me from your presence

or take your Holy Spirit from me.

Restore to me the joy of your salvation

and grant me a willing spirit, to sustain me (Psalm 51:1–12).

|

David and Bathsheba by Ernst Fuchs (1984-1985). |

Given that most ancient peoples divinized their kings and sanitized their faults, and that the Hebrews included rather than whitewashed this episode from their sacred history, David's public confession is shocking in its candor. Perhaps it was this candor that led Christians to honor David almost a millennium later as "a man after God's own heart" (Acts 13:22).

David appeals to God's unfailing love and immense compassion for forgiveness of his sins. His language suggests a fixation of sorts on his multiple failures: "For I know my transgressions, and my sin is always before me." He admits that he has not only wronged his neighbor and befouled himself but, more importantly, dishonored God. David prays for release from this fixation on his sinful actions (plural), including cleansing, renewed joy, and a steadfast spirit to sustain him amidst the deep discouragement people can feel when hounded by their moral failure.

In her many works Joan Chittister, a Benedictine nun and author of some twenty-five books, returns time and again to the themes of personal failure and struggle. One mistake we often make, she suggests, is to accept perfection as our standard or goal. When we imagine that we will never fail, failure hits hardest. Perfection is an oppressive standard, and no Christian this side of heaven will ever reach it: "The problem, of course, is that we fail. We know ourselves to be weak. We stumble along, being less than we can be, never living up to our own standards, let alone anyone else's. We eat too much between meals, we work too little to get ahead, we drink more than we should at the office party. We're all addicted to something. Those addictions not only cripple us, they convince us that we are worthless and incapable of being worthwhile. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy of the worst order because it traps us inside our own sense of inadequacy, of futility, of failure." David's adultery and de facto murder were regrettable, but they were not remarkable. Such imperfections are our common lot.

|

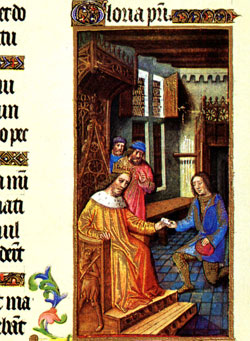

David sends Uriah to the front lines of battle. |

In fact, his penitential poem hints at a deeper malady. Not only does David ask forgiveness for his sinful actions (plural), he laments his sinful disposition (singular): "Surely I have been a sinner from birth, sinful from the time my mother conceived me." While David's sinful actions might be thought of as acute or episodic choices of free will, his inclination to sin results from a chronic and congenital condition. His problem, to draw upon a medical model, is that his sinful inclinations are inherited rather than acquired. This led St. Augustine to his famous diagnosis that when left to themselves human beings are "not able not to sin" (non posse non peccare). Everything we know about human experience confirms this.

Knowing that moral failures have their root in an inherited sinful disposition, rather than the other way around as we often and wrongly believe (that is, I develop a sinful nature by committing sinful actions), can be unsettling. As the Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1915–1968) observed: "The basic and most fundamental problem of the spiritual life is this acceptance of our hidden and dark self, with which we tend to identify all the evil that is in us."

The perennial temptation at this point, given the insecurities provoked by both admission of failure and the realization of a darker impulse that gave rise to them in the first place, is to deny, rationalize, or engage in a personal makeover. This is a natural and understandable reaction, but it gets us nowhere. Every person longs to be loved and accepted for just who they are and where they are, and that is precisely what God offers us, but as Frederick Buechner writes, "that is often just what we also fear more than anything else....Little by little we come to accept instead the highly edited version which we put forth in hope that the world will find it more acceptable than the real thing." True saints are those who realize, like David, just how unsaintly they can be in both action and disposition, and who do not try to pretend otherwise, or put on appearances to mask reality, either to themselves or to others.

|

Illustrated manuscript of Psalm 51 (13th century). |

In addition to honesty and candor about our fallen condition, David points us to another lifelong virtue, the spirit of contrition: "The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise" (Psalm 51:17). Contrition does not imply self-hatred or wallowing in failure. David does neither. Instead, we seek that place where we view failure as "among the best friends of the soul." Rather than chasing unattainable perfection, says Chittister, we should appropriate the "sanctifying nature of mistakes." It is a humbling but ultimately liberating notion to believe with St. Augustine that "even from my sins God has drawn good."

The season of Lent reminds us of the seriousness of the sinful actions we commit, and the sinful disposition we inherited that gives rise to those failures. Lent beckons us to candor and contrition. But losing hope is more serious still. "Should we fall, we should not despair and so estrange ourselves from the Lord’s love," encouraged St. Peter of Damaskos (12th century); "let us always be ready to make a new start. If you fall, rise up. If you fall again, rise up again." We get up again, Buechner suggests, because Christians are "people who have been delivered just enough to know that there’s more where that came from, and whose experience of that little deliverance that has already happened inside themselves and whose faith in the deliverance still to happen is what sees them through the night."

For further reflection:

* What does Augustine mean: "not able not to sin."

* Buechner suggests that we "edit" our image to find greater acceptance. Do you agree?

* What does David mean by a "broken spirit and heart?"

* Consider the distinction between sinful acts and a sinful disposition.

* What does Chittister mean by "the sanctifying nature of mistakes," and that failure is "among the best friends of the soul"?