Race and Repentance:

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

For Sunday January 27, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 9:1–4

Psalm 27:1, 4–9

1 Corinthians 1:10–18

Matthew 4:12–23

|

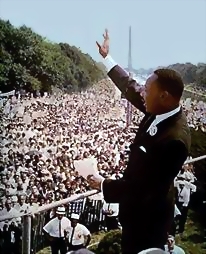

King's "I Have a Dream" speech, August 28, 1963, in Washington. |

Two weeks ago the Obama 2008 campaign opened its Palo Alto office down the street from our house. I hope the presidential campaigns don't argue whether gender or race is more important, and that they address a breadth and depth of issues, but every time I pass by their office I wonder: Is America ready to elect a black man as president?

And not just any black man, but the multi-racial Barack Hussein Obama. A man who was born in Honolulu to a white mother from Wichita and a black father from Kenya. Whose Indonesian step-father took their family from Honolulu to Jakarta when he six. A man whose Muslim-Arabic name conjures up associations with a pathological dictator and the world's most dangerous terrorist. The first black to be elected as president of the Harvard Law Review, and our country's only currently serving black senator.

Is America ready to take another step beyond its racist history? It's a provocative question for 2008, when we'll commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. It's also a provocative question because in some ways, despite significant progress, our country is still deeply racist. Racial reconciliation and equality in a comprehensive sense — relational, structural, economic, political, educational, etc. — remain unfinished tasks.

Consider the movie Crash, which won three Oscars in 2006, including best picture. The story opens with a car wreck that symbolizes the collisions between ordinary people because of their racist rage. This rage lies just beneath the surface of nearly every aspect of our identity — our ethnicity, our English slang or accent, work, dress, music, marriage and family. A Persian shop keeper ("They think we're Arabs!"), a Hispanic locksmith, two black hoodlums, a wealthy black film director, redneck white trash, a despicable suburban white couple, a naive white rookie cop, and other ethnic typecasts are all haunted by stereotypes that they project onto others, paranoia (not all of which is unjustified), bigotry, and mutual misunderstanding. Director Paul Haggis does an especially good job of depicting racism not only between people who are "different" but also among people of the same groups.

|

Click here to read King's "I Have a Dream" speech. |

Matthew writes that "Jesus began to preach, 'Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near'" (4:17). Those are the exact words that the wild and wooly John the Baptizer preached in the parched desert of Judea and at the shores of the Jordan River (3:1). In Mark's parallel account they're the very first words spoken by Jesus (1:15).

To repent, says John Howard Yoder, is not to feel bad, but to think differently. To repent doesn't mean to grovel in self-hatred or pious sorrow. When you repent you turn around, change directions, choose a different path, or make a radical rupture. Repentance signals an abrupt end to life on auto-pilot or to business as usual.

That's exactly what happened when Jesus called two sets of brothers. When Jesus saw Peter and Andrew fishing in the Sea of Galilee, he invited them, "Come, follow me." Matthew and Mark dramatize their unequivocal response: "At once they left their nets and followed him." Jesus then saw James and John fishing with their father Zebedee, and likewise called them. "They immediately left the boat and their father and followed him." A year or so later, speaking for the twelve apostles, Peter could even say to Jesus, "We have left everything to follow you!" (Mark 10:28).

Why such urgency and abandonment? Why not go home and talk it over with the family? Won't friends think we're crazy, impulsive, even irresponsible? Won't you regret such a categorical decision? Why not hedge your bet? In the epistle this week Paul admits that from a human perspective the call of Jesus to repentance is both "foolish" and "scandalous" (1 Corinthians 1:18, 23).

Jesus invited Peter, Andrew, James and John to reorient their lives by following him because in his own person "the kingdom of God has arrived." Jesus both announced and embodied God's rule or reign on earth, right here and right now. There was an unmistakable element of cosmic fulfillment in his preaching, teaching, and healing: "The kairos has come. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the good news!"

|

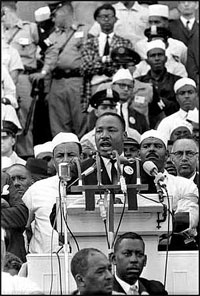

December 10, 1964, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize |

The Greek word kairos denotes a critical juncture, a divine intervention, or a special moment, in contrast to chronos or everyday clock time. You plot chronos on your calendar, like the soccer game on Tuesday at 4:00 PM. With chronos you might procrastinate with minimal consequences. Kairos is different. Because kairos denotes a unique opportunity, it invites a radical response, an urgent choice, or a fundamental reorientation. Peter, Andrew, James and John sensed God's kairos, and so they left everything at once to follow Jesus — their father, the hired help, the boat, their nets, their livelihoods, everything that was safe, predictable and familiar.

In stark contrast, Jesus lamented that Jerusalem “did not recognize the kairos of God's coming to you” (Luke 19:44). It's one thing, he warned, to be able to predict the signs of the seasons or the weather, but quite another to recognize and act upon the "signs of the kairos" (Matthew 16:3).

Throughout the Bible, peripheral outsiders who are marginalized by mainstream insiders connect with Jesus's urgent invitation — the religiously suspect, the ethnic enemy, social outcasts, the economically poor, and the morally impure. Smug establishment people often reject the invitation, don't believe it, or choose not to hear. A wealthy businessman, for example "went away sad" when Jesus invited him to "Come, follow me" (Mark 10:22). The pagan Ninevites, on the other hand, understood the kairos of God. Much to Jonah's shock and chagrin, those "foreigners" responded to his preaching, repented, and believed his message about Yahweh.

Racial reconciliation is central to the Gospel. Paul even describes the work of Christ as one of reconciliation between warring factions (in his day, Jews and Gentiles): “For He himself is our peace, who has made the two one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility. . . . His purpose was to create one new man out of the two, thus making peace, and in his one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility” (Ephesians 2:14–16). New Testament images of heaven are gloriously multi-ethnic: “I looked and before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb” (Revelation 7:9).

|

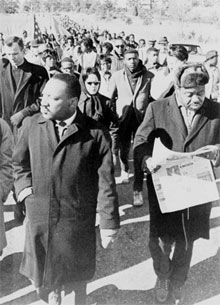

From Selma to Montgomery, Alabama (1965). |

Part of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s many-faceted genius was his recognition that chronos, mere clock time — the passage of days, weeks, and years, no matter how long or short, no matter how trivial or important — is no match for kairos, that opportune moment of God's visitation. He knew that since racial reconciliation is part of the Gospel, the Gospel necessarily has political ramifications. His life and ministry, and the larger role of the black church, are instructive.

Lerone Bennett points out in his book Before the Mayflower how toward the end of the nineteenth century the black church “quickly established itself as the dominant institutional force in black American life.” King himself was a churchman, and there was never a time when he was not a pastor — at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, then Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. He once described himself as "the son of a Baptist preacher, the grandson of a Baptist preacher, and the great grandson of a Baptist preacher. The Church is my life and I have given my life to the Church” (Mervyn Warren, King Came Preaching).

King wisely understood that the power of the pulpit wielded a two-fold function: pastoral mediation — to reconcile people to God and to one another; and prophetic exhortation — to bring the Gospel to bear on one's contemporary culture. In King, writes Mervyn Warren, “the man and the moment met; he made a Christian decision on behalf of social, economic and political justice, and the world was changed.” Only time will tell if Obama, or any other candidate, might embody a new prophetic message for our own political moment.

For further reflection:

* Can you recall a time when you truly repented? Or resisted repenting?

* When have you experienced moments of kairos that interrupted chronos?

* What have been your experiences, positive or negative, of racial reconciliation?

* For Obama's Christian experience see "My Spiritual Journey". This is an excerpt from his book The Audacity of Hope published in Time magazine (October 16, 2006).

Image credits: (1) Nostalgia Central; (2) American Rhetoric; (3) d@dalos website; and (4) The Library of Congress' America's Library website