Jesus Wept:

Fifth Sunday in Lent 2008

For Sunday March 9, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Ezekiel 37:1-14

Psalm 130

Romans 8:6-11

John 11:1-45

|

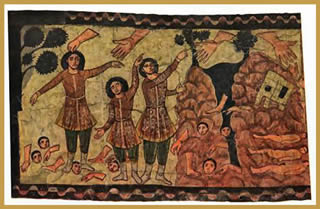

Third-century fresco of Ezekiel 37, the Dura Europas synagogue in Syria. |

In 2005 when my wife and son visited France, they left the beaten tourist track to explore the Paris catacombs. In 1786 Monsieur Thiroux de Crosne, Lt. General of the Police, and Monsieur Guillaumot, Inspector General of the Quarries, converted some Roman limestone quarries into a subterranean cemetery. In nearly 200 miles of dark and dank tunnels Parisians meticulously stacked the skeletal remains of five million people from floor to ceiling in various symmetrical patterns. Graffiti line the narrow passages and low ceilings, commenting on the certainty of death and the uncertainty of life: "Crazy that you are, why do you promise yourself to live a long time, you who cannot count on a single day?"

In an ancient Semitic version of the Paris catacombs, the prophet Ezekiel envisioned the nation of Israel as a wasteland of bones scattered across a desert valley (Ezekiel 37). Lifeless, windswept, and eery, the "great many bones that were very dry" symbolized Israel's exile to pagan Babylon: "Son of man, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, 'Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off'" (37:11). In short, Israel felt hopeless.

|

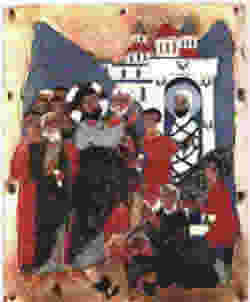

The raising of Lazarus. |

Helpless and hopeless is exactly how Mary and Martha felt when their brother Lazarus died (John 11). And a nagging question added insult to their injury. The sisters, their family, and their neighbors were so flummoxed by the question that John repeats it three times in his story. It's the sort of question an ancient Hebrew who had been exiled to Babylon would have asked the priest and prophet Ezekiel: "Can these lifeless bones live again?" It's a question that we all ask even today.

Couldn't God have prevented this tragedy in the first place?

Couldn't God have saved Israel from Babylon? Or healed Lazarus of his sickness like he healed so many other people?

When her brother Lazarus took sick, Mary asked Jesus for help. But Jesus purposely delayed intervening, so by the time they finally arrived back home in Bethany, Lazarus had been dead and buried for at least four days. "Lord," Martha cried, "if you had been here, my brother would not have died" (John 11:21). Mary her sister said the exact same thing: "Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died" (John 11:32). Amidst all the grief and tears, the neighbors mumbled their own aside: "Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?" (John 11:37). Could he not have prevented all this horrible pain and heartache?

|

Image of the raising of Lazarus from a Roman catacomb. |

Jesus didn't answer their question. Instead, in the shortest verse in the entire Bible, He revealed one of the most important characteristics we can ever learn about the heart of God: "Jesus wept" (John 11:35). When Jesus experienced the sisters Mary and Martha weeping for their dead brother Lazarus, and their distraught neighbors, John writes that he was "deeply moved in spirit and troubled" (John 11:33). The God whom Christians worship is not a remote and aloof "sky god" somewhere way out there. No, He's a tender God who is deeply moved, even grieved, by anything and everything that threatens our human well-being.

This compassionate and empathetic nature of God is the reason why the Scriptures encourage us to bring to Him every anguish, confusion, anger, perplexity, and anxiety. When my friend Luke lost a second child in a car accident, I remember at the memorial service how he resonated with the Hebrew Scriptures where the saints threw dust in the air and cried out in pain. Stoicism is not a Christian virtue. Like Mary, Martha, and their neighbors, the Psalmist for this week demonstrates this sort of visceral scream to God (Psalm 130:1–2):

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord;

O Lord, hear my voice.

Let your ears be attentive

to my cry for mercy.

We can pray to God like this because we know that He weeps when we weep. We place our hope in Him because, as the Psalmist continues, He is a God of "unfailing love" and "full redemption" (Psalm 130:7).

|

Image of the raising of Lazarus from a Roman catacomb. |

God doesn't only empathize with our many pains and sorrows. He also acts. Jesus wept with Mary and Martha, and then he raised Lazarus from the dead (his last miracle before his own death and resurrection). Of course, human experience tells us that God doesn't act exactly when, where, and how we think He should act. So we must wait in hope. The Psalmist cries out to God with full confidence in His compassionate love, but even so, his poem repeats five times, perhaps talking to himself, that he must "wait" like a sentinel on the night shift who waits for the sun to rise (Psalm 130:5–6).

Part of Christian maturity involves learning to wait. We ought to be confident not so much about our chances for a rosy outcome, or about exactly where, when and how God will act, but confident that He will act. We wait in hope even while we "cry out of the depths" to God. The alternative is to lose hope and to spiral into despair, which was the chronic temptation for Ezekiel and the exiles: "Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off" (Ezekiel 37:11). However tempting, however human, however understandable, hopeless despair is not a Christian place to live.

|

Raising of Lazarus, 12th century enamel plate from Georgia. |

For further reflection:

* Meditate: "For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet without sin. Let us then approach the throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and grace to help us in our time of need" (Hebrews 4:15–16).

* Consider that Jesus “destroyed death and brought life and immortality to light through the gospel ” (2 Timothy 1:10).

Image credits: (1) Biblische Ausbildung; (2) Christian Theological Seminary; (3) & (4) Belmont University, Roman catacomb art; and (5) Georgian Art, Past and Present.