Sacred Scripture, Violent Verses:

How Should We Read the Bible's Texts of Terror?

For Sunday July 15, 2012

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Samuel 6:1–5, 12b–19 or Amos 7:7–15

Psalm 24 or Psalm 85:8–13

Ephesians 1:3–14

Mark 6:14–29

There's lots of talk these days about Islamic violence, but the lectionary readings for the last month show how sacred violence is deeply embedded in our holy scriptures.

"The Lord put Saul to death" because he showed mercy to the Amalekites and their king Agag (1 Chronicles 10:14, 1 Samuel 15).

|

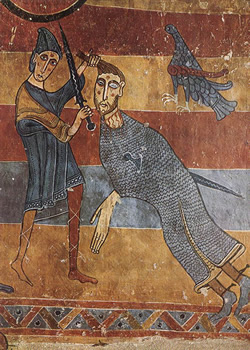

David beheads Goliath, 12th century mural from Catalonia. |

God has commanded Saul to "attack the Amalekites and totally destroy everything that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys" (1 Samuel 15).

After his death, the Philistines mutilated Saul's corpse. "The next day, when the Philistines came to strip the dead, they found Saul and his three sons fallen on Mount Gilboa. They cut off his head and stripped off his armor, and they sent messengers throughout the land of the Philistines to proclaim the news in the temple of their idols and among their people. They put his armor in the temple of the Ashtoreths and fastened his [decapitated] body to the wall of Beth Shan" (1 Samuel 31:8–10; cf. 1 Chronicles 10:10).

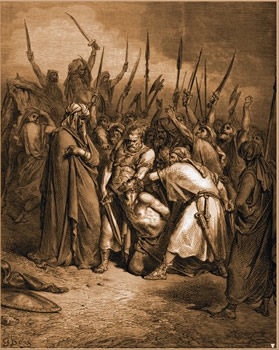

Samuel then made amends for Saul's misguided mercy; he "hewed Agag in pieces before the Lord" (1 Samuel 15:32–33).

David beheaded Goliath, then "took the Philistine's head and brought it to Jerusalem" (1 Samuel 17).

The readings this week provide two more grisly texts. When Uzzah reached out to steady the ark of God, "the Lord's anger burned against Uzzah because of his irreverent act; therefore God struck him down and he died there beside the ark of God" (2 Samuel 6).

And in the gospel reading, Herod beheaded John the Baptist after a dinner party dare (Mark 6).

|

"Samuel hewed Agag in pieces before the Lord." |

There are many more and even worse violent verses in the Bible, like Deuteronomy 7:2 and 20:16–17: "You must destroy them totally. Make no treaty with them, and show them no mercy… Do not leave alive anything that breathes — completely destroy them." In Numbers 25 the priest Phinehas was praised for his zeal when he slaughtered an Israelite and a Midianite woman with a single thrust of his spear. Today the Eastern Orthodox church celebrates Phinehas as a saint every year on September 2. We could produce more examples; in his recent book Laying Down the Sword; Why We Can't Ignore The Bible's Violent Verses (2011), Philip Jenkins, professor at Penn State, has a table that lists what he considers the nineteen "most disturbing conquest texts."

Back in 1984 Phyllis Trible coined a phrase for the title of her book that ever since has served as a proxy for violent verses like these — she called them "texts of terror." Her book explores the humiliation of four women: Abraham and Sarah's slave Hagar (Genesis 16:1–16; 21:9–21); Jephthah's unnamed daughter, his only child, who is killed by her own father as a human sacrifice (Judges 11:29–40); the gang-rape and murder of an unnamed concubine by the men of Benjamin (Judges 19:1–30); and Tamar, who was raped by her brother Amnon (2 Samuel 13:1–22).

Today we would call these texts of terror genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes. Yes, the Bible is a bloody book.

These stories aren't a new problem; the earliest believers struggled with them. Down through the centuries readers have developed numerous strategies to interpret these texts. Most of these strategies contain elements of truth, and are partly helpful. But none of them are fully satisfying. At the end of the day the texts of terror remain part of our Christian canon of scripture.

Most believers ignore these texts as having little practical relevance for their lives. We naturally gravitate toward passages like Jesus's Beatitudes. Jenkins observes how even a three-year cycle of weekly Bible readings like the Revised Common Lectionary omits the texts of terror. In theory, all Scripture is equally important, but in practice most of us invoke a "canon within the canon" — consciously or unconsciously, we privilege some parts of the Bible over others. Still, we ignore the texts of terror at our peril, because many believers have used them to justify their own violence.

|

Beheading of John the Baptist by Caravaggio. |

A religion is more than its texts, and so many readers emphasize God's perfect character over a finite human text (however sacred). An early bishop named Marcion (c. 85–160) rejected the violent deity of the Old Testament in favor of the heavenly father of Jesus. A contemporary example of a similar outlook is Robert Wright's book The Evolution of God (2009). Wright argues that religion has evolved from the barbaric polytheistic deities of the Stone Age to the benevolent monotheistic god of the three Abrahamic faiths.

It's obvious that the crude stories of sacred violence reflect the savagery of their ancient cultures. They're no worse than what every people or religion did back then — or today. When Jonah preached to the Assyrian Ninevites, for example, he was going to a people that "scorched its enemies alive to decorate its walls and pyramids with their skin" (Ellul).

Related to this is the observation that these violent verses are historical descriptions of tragic events, not moral prescriptions for us to follow today. The violent acts of minority extremists are rare exceptions, and don't represent the core values of a religion's mainstream majority.

Early Christian exegetes like Origen (185–254) employed allegorical interpretations that de-emphasized the literal meaning. Many readers today read the Bible for spiritual or moral meanings. Many Muslims similarly insist that the true jihad or holy war is waged in the inner soul rather than against external enemies.

Others appeal to God's wisdom that's incomprehensible and inscrutable to mere mortals. Who are we to question the Almighty? Job 38–41, for example, is a withering divine interrogation of over seventy questions that God puts to Job. Any number of Biblical texts echo Isaiah 55:8, "For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways," declares the Lord.

|

The death of Uzzah and the Ark of God. |

Some readers say that the Canaanites were evil and deserved their fate, but this is a dangerously self-justifying strategy.

Finally, many interpreters read these texts with a greater or lesser degree of historical scepticism and not as reliable eyewitness reportage. Since these texts were written about five hundred years after the purported events, and since they enjoy little to no archaeological support, Jenkins says that we should "treat these stories with real [historical] scepticism." He urges us to dig deeper for a core message: "The imagined war against outside peoples and customs symbolized a rejection of any and all things that distract or separate a people or an individual from God" (224). For Jenkins, that "core truth" is the fundamental implication of radical monotheism — the absolute God deserves unconditional obedience from his chosen people.

However helpful these strategies of selective editing are, Jenkins arrives at a surprising conclusion — they aren't necessary. Instead of avoiding the violent verses or explaining them away, we should read, absorb, comprehend, and even preach these texts of terror. And in a line of argument that he mentions but doesn't develop, he quotes Rene Girard of Stanford whose important work on religious violence has argued that the Bible is the first text to present sacred violence from the perspective of the victim, and thus, paradoxically,"it is for biblical reasons that we criticize the Bible" (7, 240). That might be about as good as it gets when it comes to texts of terror.

Image credits: (1) ReligiousReading.com; (2) ScienceOfCorrespondences.com; (3) Love in the Ruins blog; and (4) Living the Gospel blog.