At Least He Was Honest:

The Rich Young Ruler

For Sunday October 14, 2012

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Job 23:1–9, 16–17 or Amos 5:6–7, 10–15

Psalm 22:1–15 or Psalm 90:12–17

Hebrews 4:12–16

Mark 10:17–31

I've always loved the rich young ruler as a sympathetic anti-hero. He's young, wealthy, powerful, and spiritually earnest. He asks the right questions. But his story comes to a bad end, and so he's not a traditional hero.

When he asked what he must do to inherit eternal life, Jesus shocked him with a challenge he couldn't have anticipated: divest yourself of all your wealth, distribute it to the poor, then follow me in my peripatetic ways. That was too much, and so the story concludes: "he went away sad."

|

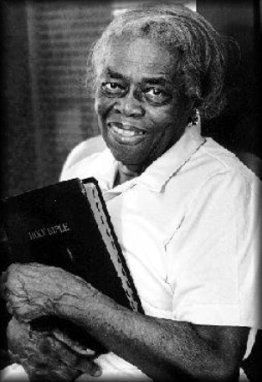

Oseola McCarty. |

In fact, many wealthy people have answered this call of Jesus. We owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude for their obedience and generosity. They did not flinch or blink.

Melania the Elder (d. 411) is one of my spiritual heroines. Born to an aristocratic family in Spain, at the age of twenty-two she was widowed, had lost two sons, and was one of the richest women in the Roman Empire. In her early thirties she hired a trustee for her remaining son, then sailed to Alexandria. There she sold her possessions, "changed her holdings into gold," and spent six months "making the rounds of the desert and seeking out the holy men."

In Jerusalem she built a monastery and befriended another wealthy aristocrat named Rufinus: "And so for twenty-seven years they both entertained with their own private funds the bishops, the solitaries, and virgins who visited them… So much wealth did she spend in holy zeal." Churches, monasteries and prisons were her beneficiaries, indeed, "no one failed to benefit by her good works."1

I wonder what happened to the rich young ruler. The early church prized his story so much that it occurs in all three synoptic gospels. Whereas it's easy to take a cheap shot at rich people, the gospel says that "Jesus looked at him and loved him." I think this is because he was straight up honest, with himself and with Jesus. He didn't try to have it both ways. There were no rationalizations about special circumstances, no pious excuses, no attempt to negotiate a compromise. He counted the cost, looked at his life, and turned his back on Jesus. He was married to his money; divorce was impossible.

A few weeks ago I failed a much easier test when a beggar asked me for help in the Costco parking lot. I turned him away, and as I did, I felt my heart shrivel a little. A few days later I was grateful for a do-over at the farmer's market. I've thought a lot about those two experiences in light of this week's gospel. What was going on? Was I really worried about $5? Surely there were deeper issues. One thing's for sure; whereas I might have helped the poor with a small handout, the poor definitely helped me with an opportunity to imitate God's generosity.

In his new book What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (2012), Michael Sandel of Harvard laments how markets and market values have triumphed over all other competing values. In the last thirty years, we've gone from "having" markets to "being" a market.

Today you can buy and sell almost anything. Immigrants can buy permanent residence in the US if they invest $500,000 and create ten jobs in areas of high unemployment. Lobbyists in Washington, DC, pay line-standers to secure seats at congressional hearings. School districts pay children for academic performance. Project Prevention pays women drug addicts $300 cash if they agree to sterilization or long-tern birth control.

The results have been devastating. "In a society where everything is for sale, life is harder for those of modest means. The more money can buy, the more affluence (or the lack of it) matters."

Sandel gives dozens of examples of how market values dominate our lives. He also explains how we got to this point. Traditional economics ignore or oppose ethical values. Some people argue that unregulated markets are the best means to all public ends. Ayn Rand still commands a wide readership. She criticized self-sacrifice for the public good as the greatest sin, and commended radical individualism and selfishness as the greatest virtues.

These trends are aggravated by two factors, says Sandel — the persistent prestige of market thinking despite the devastation of the 2008 crash, and "the rancor and emptiness of our public discourse," along with "the moral vacancy of contemporary politics." Sandel's book tries to reconnect markets and morals.

That's one of the challenges I faced in the Costco parking lot. To accept Jesus's challenge to the rich young ruler, to desacralize your money by divestment like Melania the Elder, you face an uphill battle against powerful and prestigious cultural forces. You must swim against the tide, mainly by yourself. If we can't imitate Melania, at least we can follow the rich young ruler and be honest about the struggle. "To be sane in a mad time / is bad for the brain, worse / for the heart" (Wendell Berry).

Economic forces and prevailing political winds will always threaten to brainwash us, but they don't fully explain my reaction to the beggar in the parking lot. That would be a convenient excuse. At some deeply personal level I bear my own responsibilities. But like those large external and institutional forces, the inner recesses of the human heart are complex. Back in the fourth century John Cassian surveyed many monasteries. One thing that amazed him was how monks who had renounced great wealth could nevertheless fly into a rage over a lost pen or a borrowed book.

In his poem "The Dream," Wendell Berry imagines reclaiming nature from industrial humanity, but then he has an epiphany: "I see that my mind is not good enough. / I see that I am eager to own the earth and to own men. / I find in my mouth a bitter taste of money, / a gaping syllable I can neither swallow nor spit out." And in "Voices Late At Night," he utters an ironic prayer: "Until I have appeased the itch / To be a millionaire, / Spare us, O Lord, relent and spare; / Don't end the world until it has made me rich."

Battling the spirit of the age is hard enough; conquering the depths of desire is harder still. And the invitation of Jesus is given to all of us, and not just to rich powerbrokers.

|

St. Melania the Elder. |

Oseola McCarty (1908–1999) of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, was one of those rare individuals who subverted social expectations and disciplined her desires. After dropping out of school in the sixth grade, for the next 78 years she washed and ironed the dirty laundry of white people. She never left the home where she was raised, she never married, never had any children, and never drove. Her TV got one channel, but that didn't matter because she rarely watched it. Late in life she bought a window air-conditioner, but only used it when guests visited. She always lived alone after her aunt died in 1967.

On July 26, 1995, when she was 87, McCarty gave $150,000 to the University of Southern Mississippi to endow scholarships for black students. Thirty years earlier, USM didn't even admit black students.

"I would go to school and come home and iron. I'd put the money away and save it. When I got enough, I went to First Mississippi Bank and put it in. The teller told me it would be best to put it in a savings account. I didn't know. I just kept on saving."

After her aunt died in 1967, she made a plan to give away her life savings. She contacted an attorney, then went to her bank. An official laid out ten dimes on a table. He explained that she could indicate how much she wanted to leave to various people by placing the appropriate number of dimes on each of their names that were written on scraps of paper. She gave three "dimes" to her cousin, one to her Friendship Baptist Church, and six to USM.

"I live where I want to live, and I live the way I want to live. I couldn't drive a car if I had one. I'm too old to go to college. So I planned to do this. I planned it myself," she told the New York Times.

Oseola McCarty reminds me of Melania the Elder. Both women followed in the footsteps of Peter, who after hearing Jesus's words to the rich young ruler said, "Lord, we have left everything to follow you."

[1] From the "Lausiac History" by Palladius.

Image credits: (1) Antiochian.org and (2) AllisonJ.org.