Poverty Reduction — Of the Soul

The Parable of Dives and Lazarus

For Sunday September 29, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 32:1–3, 6–15 or Amos 6:1–7

Psalm 91:1–6, 14–16 or Psalm 146

1 Timothy 6:6–19

Luke 16:19–31

Hardly a month goes by without some mention of the growing gap between the rich and poor. There are important disagreements about the causes, consequences, and solutions of radical inequality, but the reality of it is undeniable. Consider two recent studies.

In his book Who Stole the American Dream? (2012), the Pulitzer Prize-winner Hedrick Smith argues that in the last thirty years "we have become Two Americas." A "gross inequality of income and wealth" has demolished the middle class dream. This wasn't inevitable, says Smith. It's not the result of "impersonal and irresistible market forces." Rather, it's the consequence of government policies and corporate strategies.

|

Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize-winner and former chief economist for the World Bank, comes to similar conclusions in The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (2013). He writes, "The top 1 percent of Americans gained 93 percent of the additional income created in the country in 2010, as compared with 2009." Like Smith, he says this didn't have to happen.

The issue here isn't one of envy. Rather, Stiglitz fears that gross inequality threatens the very nature of civil society — our politics, health care, education, housing, employment, legal system, etc.

Problems are worse in the rest of the world. According to the World Bank, in 2010, 2.40 billion people lived on less than $2 a day. The bitter irony here is that there's been significant progress in poverty reduction in the last thirty years. But look at the yardstick — $2 a day!

These people could live for two days on my Starbucks latte. They suffer the catastrophic consequences of poverty as measured by a broad array of indices — access to safe and dependable water, life expectancy, infant and maternal mortality, literacy, and so on.

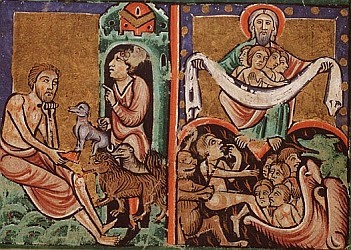

This is an old story. Luke's gospel for this week describes the economic disparity between an unnamed rich man and a beggar named Lazarus (not to be confused with the brother of Mary and Martha). The rich man later became known as "Dives," which is the Latin for "rich man" that Jerome used in his late fourth-century translation of the Bible.

The story begins with the words, "there was a rich man." This is exactly how the previous parable in Luke 16 about the Shrewd Manager begins: "There was a rich man." Jesus didn't hesitate to use money as a measure of our spiritual health.

|

The first parable is told from the perspective of the rich manager, and ends with a warning to people who "loved money" that "you cannot serve God and Mammon." This week's story takes the vantage point of the poor Lazarus, and ends with a radical reversal of fortunes.

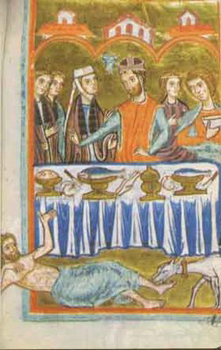

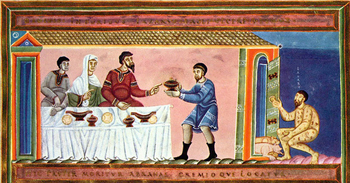

Dives dressed in the finest clothes. He ate the best food. Luke says that he "lived in luxury every day." And every day he actively ignored the poor man at his gate.

Lazarus was chronically hungry. He wore rags. He was covered with lesions. And as much of the art about this parable emphasizes, the dogs licked his sores.

Then death came to both men, as it will to each one of us. In the afterlife, Lazarus found comfort. The rich man suffered torment, agony and regret.

In life, Lazarus begged the rich man for help. In the afterlife, it was the rich man who begged Lazarus for mercy on both himself and his family that was still alive. But it was too late. What was done was done.

As in life, now in death, a huge gulf separated the two men. Luke describes a "great chasm" between Lazarus and Dives, only now their fortunes had flipped.

The parable reminds me of a story about the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968). When one of his students asked whether the snake literally spoke in the Garden of Eden, Barth responded, “The important point is not whether he spoke, but what he said.”

I don't think Luke intends to describe the furniture of heaven or the temperature of hell. Whether you read this as a parable or a literal description of the afterlife, the point is the same.

Jesus warns us that our time is short. Our opportunities to serve the poor don't last forever. Our economic choices shape our deepest identities and our eternal destinies. The tragic realization of Scrooge in Charles Dickens's "Christmas Carol" comes to mind: "These are the chains I forged in life."

But tragedy isn't a necessity. In the language of this week's epistle, by sharing generously and being rich in good deeds, we "lay up treasure for ourselves as a firm foundation for the coming age," and "take hold of the life that is truly life."

It might make me feel good, but disparaging the rich is a sign of sanctimony. Thank God for the wealthy women who supported Jesus (Luke 8:2–3), for the rich man Joseph of Arimathea who tenderly buried him, and for all the wealthy saints today who follow their footsteps.

Wealth isn't intrinsically evil, but it's definitely dangerous. In helping the poor we acknowledge that riches can hinder our own salvation. We admit that we are susceptible to its seduction. 1 Timothy 6 describes the realm of riches as fraught with arrogance, traps, temptation, harmful and foolish desires, ruin, destruction, grief and wandering from the faith.

|

In his new book Through the Eye of a Needle; Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (2012), Peter Brown of Princeton documents the evolving attitudes and practices of Christians regarding wealth. He rejects two common myths. First, that of "the primal poverty of the early Christians." That was true for some, but not for all. And second, although the church gained new privileges under Constantine, the emperor didn't usher in a time of new wealth for the church. That didn't happen until the year 370 or so.

Until then, says Brown, the "mediocres" or "in-betweeners" were the church's biggest benefactors — the "middling people" between the super rich and the oppressed poor, like artisans, small farmers, small town clerics, tradesmen, and minor officials. Brown calls them "the solid keel of the Christian congregations through the fifth century."

There are no easy answers to the hard sayings of Jesus about money. Brown documents the many different ways believers grappled with parables like Lazarus and Dives, from radical renunciation by the super rich, the "anti-wealth" of the ascetics, care of the poor, the everyday generosity of ordinary believers, and, by the fifth century, the clerical stewardship of massive wealth as God's providential gift.

We freely share not out of guilt, ascetic renunciation (although God calls some people to that path), some communistic ideal that loathes private property, nor because the poor are virtuous. Paul is clear, "God richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment."

Rather, in serving the poor we care for our own souls by imitating the character of God himself. Only in heaven, said Mother Theresa, will we understand how much we owe the poor for helping us to love God like we should.

For further reflection

* For a short version of Stiglitz's book, see his article, Of the 1%, for the 1%, by the 1%, in Vanity Fair (May 2011): http://www.vanityfair.com/society/features/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105.

* For a beautiful art-historical essay on this parable see Margaret Duffy, The Parable of Dives and Lazarus at http://imaginemdei.blogspot.com/2012/03/parable-of-dives-and-lazarus.html.

Image credits: (1) Fish Eaters; (2) Godzdogz: The English Dominican Studentate; and (3) Pastor's blog, Luther Menorial Church of Chicago.