Keep Praying, and Don't Give Up:

The Parable of the Persistent Widow

For Sunday October 20, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 31:27–34 or Genesis 32:22–31

Psalm 119:97–104 or Psalm 121

2 Timothy 3:14–4:5

Luke 18:1–8

Have you ever felt like giving up? Throwing in the towel? Leaving the ministry, or quitting the faith?

In telling the parable of the persistent widow, Jesus acknowledges that quitting the journey is a real possibility. He was, after all, a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief. His own cry of dereliction expressed the specter of defeat.

|

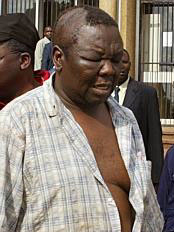

Morgan Tsvangirai. |

When Jesus scandalized some of his followers, "many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him." Jesus then asked his twelve closest followers, "Do you want to leave too?"

People quit the faith for many reasons — hypocrisy, boredom, legalistic pettiness, superficial platitudes, unanswered prayers, bitter disappointments, and intellectual doubts.

In Luke 18 Jesus encourages us "always to pray and not give up." He tells a story about a persistent widow who importuned a corrupt judge. She never gave up, despite the many injustices she experienced at the hands of the judge who "neither feared God nor cared about men."

|

Yoani Sanchez. |

There's no mysterious meaning here. The parable is straightforward. Despite our feelings of fighting a losing battle, of supporting a losing cause, don't give up. Keep praying. "Keep marching to the end," writes Bernanos in Diary of a Country Priest, "and try to end up quietly at the roadside without shedding your equipment."

In JRR Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, the elves of Lothlorien admit that they're losing their forest lands. But they battle on. They describe their struggle as “fighting the long defeat.”

In Letters of Tolkien (195), Tolkien describes our human struggle using identical language: "Actually, I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect 'history' to be anything but a 'long defeat' — though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory."

Tolkien is probably the source of the comment made by Paul Farmer, who has fought a "losing battle" for health care for the poor. In Tracy Kidder's biography of Farmer called Mountains Beyond Mountains, Farmer says, “I have fought the long defeat and brought other people on to fight the long defeat, and I’m not going to stop because we keep losing. Now I actually think sometimes we may win. I don’t dislike victory… We want to be on the winning team, but at the risk of turning our backs on the losers, no, it’s not worth it. So you fight the long defeat.”

|

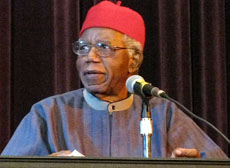

Chinua Achebe. |

In his emotionally volatile poem The Collar, George Herbert considered quitting faith and the ministry. Born to wealth and privilege, Herbert forsook a faculty post at Cambridge University and public service as a Member of Parliament, and in 1629 became the rector at Bemerton, a small village near Salisbury. He spent the rest of his short life as a country cleric, despite the protests of his friends and family that it was beneath his dignity.

The title of Herbert's poem evokes the stiff clerical collar that he wore; he complains that it's choking the life out of him. His tirade begins with him pounding the church altar on which he would have served the Eucharist — bam! — and screaming what many believer has felt but dared not express: "No more. I quit."

I struck the board, and cry'd, No more.

I will abroad.

What? shall I ever sigh and pine?

My lines and life are free; free as the rode,

Loose as the winde, as large as store.

Shall I be still in suit?

Have I no harvest but a thorn

To let me bloud, and not restore

What I have lost with cordiall fruit?

Sure there was wine

Before my sighs did drie it: there was corn

Before my tears did drown it.

Is the yeare onely lost to me?

Have I no bayes to crown it?

No flowers, no garlands gay? all blasted?

All wasted?

Not so, my heart: but there is fruit,

And thou hast hands.

Recover all thy sigh-blown age

On double pleasures: leave thy cold dispute

Of what is fit and not. Forsake thy cage,

Thy rope of sands,

Which pettie thoughts have made, and made to thee

Good cable, to enforce and draw,

And be thy law,

While thou didst wink and wouldst not see.

Away; take heed:

I will abroad.

Call in thy deaths head there: tie up thy fears.

He that forbears

To suit and serve his need,

Deserves his load.

But as I rav'd and grew more fierce and wilde

At every word,

Me thoughts I heard one calling, Child!

And I reply'd, My Lord.

|

Aung San Suu Kyi. |

Herbert's poem is full of images of constraint, against which he rebels — his clerical collar, cables, a cage, ropes, laws, and his stuffy suit. He chafes at the conformity imposed upon him, and dreams about a life "free as the road, loose as the winde, as large as store." Why not cut and run?

He complains that his reward for ministerial service is a harvest of thorns. He wonders if he's wasted his years. Did he miss out on life and ambition? He regrets the pleasures and privileges that he forfeited. Perhaps he should have stayed in Cambridge and London?

The poem then comes full circle. He concludes that the real "ropes," "cage," and "cables" that bind him are not the gospel or ministerial service but his own "pettie thoughts." In fact, the more "fierce and wilde" he raved, the more in his heart of hearts he "heard one calling, Child!" The poem ends with a robust recommitment of faith to "My Lord."

|

Ai Weiwei. |

The alternate reading from Genesis 32 describes a man on the run — that liar and swindler Jacob. Frederick Buechner calls Jacob's divine encounter at the river Jabbok the "magnificent defeat of the human soul at the hands of God."

In the epistle for this week, Paul describes his own persistence amidst many years of struggles. He encourages Timothy: "Continue in what you have learned and become convinced of, endure hardship, discharge all the duties of your ministry."

|

Anna Politkovskaya. |

Our own day has its own heroes of persistence despite the apparent futility of just causes — the Cuban dissident Yoani Sanchez, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, Myanmar's Aung San Suu Kyi, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, and the hundreds of Russian journalists like Anna Politkovskaya who've been murdered. In Zimbabwe, Morgan Tsvangirai keeps challenging Robert Mugabe, the 90-year-old dictator-thug who's plundered the country since 1980.

In persistence we savor small victories. We acknowledge our limited options and make the best of a bad situation. We resist despair.

Most of all, says Jesus, we keep praying, and don't give up.

Image credits: (1) Ireland.com; (2) Timeinc.net; (3) Wikipedia.org; (4) Wikipedia.org; (5) Wikipedia.org; and (6) Wikipedia.org.