My First Easter Confessors

For Sunday April 5, 2015

Easter Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 10:34–43 or Isaiah 25:6–9

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

1 Corinthians 15:1–11 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Mark 16:1–8

I've been doing a lot of doctoring recently — the dentist, the optometrist, and my internist for an annual physical. Next up is the dermatologist; I've had three surgeries for basal cell carcinoma, and a friend who was just diagnosed with stage 3 melanoma.

As I left the doctor's office last week with instructions for two follow up tests, I thought about Jane Kenyon's poem Otherwise. I love how she combines genuine gratitude for the present with brutal realism about the future.

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach. It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

According to my doctors, I'm in good health today. Thanks be to God. But Kenyon is right, it won't always be that way: "One day, I know, / it will be otherwise."

And then what?

You don't have to be religious to wonder what happens after your life succumbs to death. In his posthumous memoir called Mortality (2012), the atheist Christopher Hitchens describes how in his final days of dying from esophageal cancer, he reflected on the poetry of TS Eliot: "I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker, / And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker; / and I am afraid."

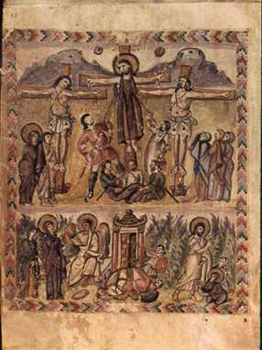

|

Harrowing of hell, Greece, 11th century. |

After my mother died in 2006, I stood alone in front of her casket at the Thomas Funeral Home in a small town in North Carolina. I twisted my neck so that my face would parallel hers. Hot tears streaked down my cheeks. My nose ran, my vision blurred. I touched mom's wrist, but it was cold and stiff.

Thanks to the mortician, she looked far better in death than she did in the last years of her life — a spitting image of her own mother, our family agreed. That made me feel good, and I was grateful for the comfort.

But I also knew that her better-than-life appearance was a death-denying cultural contrivance designed to dull my pain and distract my attention from the harsh reality that my mom was dead. Gone. No more Saturday morning phone calls to ask her about Duke and Carolina basketball, no more annual visits for her May 20 birthday that coincided with Mother's Day, no more playing Scrabble in her tiny room.

My mother's grandfather was a Presbyterian pastor in small-town Ohio. Her own mother worshipped in that church for seventy-nine years. Mom later became the organist and choir director in her own church from 1967–1992.

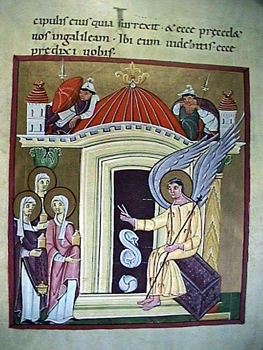

|

Three Marys at the tomb. Bamberg Apocalypse, 11th century illuminated mss. |

So, pretty much every Sunday morning for eighty years my mom joined Christians across the last two thousand years and from around the world in confessing that Jesus "suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. On the third day he rose again from the dead… I believe in the resurrection of the body and in life everlasting." In other words, the end is not the End.

"This is what we preach, and this is what you believed," Paul wrote to the Corinthians in this week's epistle. That's what my mom believed, and that's what I believed that January afternoon beside her casket.

When my father died in 1998, he donated his body to science for medical research. Eighteen months later, FedEx delivered his "cremains" to our house. I remember thinking that there had to be a better way to return such a sacred gift. I opened the box, untied the twisty that secured the plastic liner, and experienced what others had described to me. These were not fluffy ashes, but gritty shards of bone. I took a pinch of the coarse remnants of my father and rubbed them between my thumb and fingers.

When I was in high school, my father stopped going to church. He never went back. I like to think that my he lost his faith in the church as an institution but not his faith in the gospel. That was just my conjecture, my hope, until this past Christmas when my sister sent me a newspaper clipping about Galion, Ohio, the little town where I was born.

Galion was celebrating its 60th Anniversary Presentation of Handel's Messiah. Just two months after I was born, my father challenged the new choir director of the city schools to perform the Messiah. He responded, "if you get 75 people there for the first night of rehearsal, we'll do it." And that's what my dad did. On that first rainy November night in 1955, he kick-started a 60-year tradition. Their first performance of the Messiah in the high school auditorium had a chorus of 129 members.

|

Christ steps on a sleeping soldier as he rises from the tomb, England 14th century. |

Today we think of Handel's Messiah as Christmas music, but it was written for Easter. Charles Jennens wrote the libretto based on the King James Bible, and Handel famously wrote the music in a twenty-four-day period from August 22 to September 14, 1741. The work is divided into three parts and follows the church's liturgical year, beginning with Isaiah's prophecies and ending with John's cosmic doxology in the book of Revelation.

I now believe that the music of the Messiah was my father's confession of faith.

For now is Christ risen from the dead, the first fruits of them that sleep.

Since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.

Behold, I tell you a mystery; we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet.

The trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed. For this corruptible must put on incorruption and this mortal must put on immortality.

Then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written: "Death is swallowed up in victory."

O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?

But thanks be to God, who giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

If God be for us, who can be against us?

|

Stained glass window by Paolo Uccello, Duomo, Florence, 1443. |

Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by His blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing. Blessing and honour, glory and power, be unto Him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb, for ever and ever. Amen.

This Easter I follow in the faith of my first confessors, my mother and father, along with two billion other people around the world — that nothing good will be lost. Nothing evil will remain.

Isaiah prophesied that God will wipe away every tear from every face in every nation. Peter called this "the restoration of all things." Paul called it the liberation of creation from bondage to decay, and the redemption of our bodies. It's our Easter Faith, thanks be to God.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; (4) Wikipedia.org; and (5) Bible-topten.com.