From Our Archives

Michael Fitzpatrick, Treasures in Her Heart (2021).

This Week's Essay

Luke 2:49, "I had to be in my Father's house."

For Sunday December 29, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 148

Colossians 3:12–17

Luke 2:41–52

Scattered throughout our house are various baby pictures of our three children, including a few that now hang on our Christmas tree as ornaments made out of popsicle sticks. Is that what they really looked like thirty years ago? Having just celebrated the baby of Bethlehem, the gospel of Luke this week raises an irresistible question that's impossible to answer: what did Jesus look like? The earliest frescoes from the third and fourth centuries, for example, picture Jesus with short hair and clean-shaven; only later images portray him with a beard and long hair.

If you are white, American, and Protestant, your images of Jesus were probably influenced by one of the most reproduced pictures ever, The Head of Christ (1940) by Warner Sallman. One scholar estimates that Sallman's saccharine image of Jesus with blond hair, blue eyes and fair skin has been reproduced over 500 million times. The painting reminds us how easily we create Jesus in our own image.

But Jesus is always more elusive than we wish. We not only don’t know what he looked like. Luke's story about Jesus in the temple "when he was twelve years old" is all we know about him for the first thirty years of his life. Those lost or silent years are what one scholar calls a "narrative vacuum." He left not a single scrap of writing (only disappearing doodles in the sand). The gospels of Mark and John don't even include birth narratives, but begin with Jesus as an adult.

|

|

Disputation with the Doctors, Duccio di Buoninsegna, c. 1308–1311, tempera on wood.

|

There are two exceptions to this total silence. In Mark 6:3, the people in his home town of Nazareth "take offense" at Jesus because everyone knew that he was just a carpenter. And then, Luke 3:23 says that "Jesus was about thirty years old when he began his ministry." But that's it, nothing more.

Nonetheless, speculation has truly abhorred this narrative vacuum. There have been numerous theories about the first thirty years of Jesus. After all, Mary assuredly told stories about her son, as did many others.

In the centuries after Jesus, a genre of "infancy narratives" embellished the missing years of Jesus with fanciful legends. In the Infancy Gospel of Matthew (600 CE) animals speak at Jesus's nativity. In the Infancy Gospel of Thomas (c. 140–170), which Anne Rice utilized in her fictional Christ the Lord (2005) that is narrated by a seven-year-old Jesus, Jesus curses a playground bully, who consequently dies, then raises him to life with a spontaneous wish-prayer. He turns clay pots into flying birds. In the Arabic Infancy Gospel (sixth century?) Jesus's diaper heals people, and his sweat cures leprosy. Still other fables claim that when Jesus was twelve he sailed to England with Joseph of Arimathea and built a church near Glastonbury to honor his mother Mary, or that between the ages of twelve to thirty he studied in India, Persia, or Tibet.

Most of the early church, and virtually all of modern scholarship, has dismissed these tall tales as spurious. Instead, they have followed the gospel writers in being content with ignorance and silence. It's a truly remarkable demonstration of restraint. This silence about the hidden years of Jesus suggests that the early believers were not gullible or naive regarding sensationalist exaggerations about miracle stories.

The one exception to our ignorance about the first thirty years of Jesus's life is Luke's story of the twelve-year-old Jesus in the Jerusalem temple, and it is much more prosaic than we might wish.

|

|

Disputation, 15th century, Kraków. Note the sword in the heart of Mary.

|

Luke writes that every year Joseph and Mary made the 150-mile roundtrip from Nazareth to Jerusalem in order to celebrate the Feast of Passover. About twenty miles into the return trip to Nazareth, his parents discovered that Jesus was missing from their caravan of family and friends. Any parent can imagine the terror that they felt when they couldn't find their child.

After a second day to return to Jerusalem, on the third day they found the boy Jesus in the temple, "sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions." When Mary rebuked him, it became apparent that Jesus was not accidentally lost, but that he had deliberately stayed behind: "Didn't you know that I had to be in my Father's house?" Mary and Joseph didn't understand this cryptic response. After their safe return to Nazareth, Jesus "was obedient to them… [He] grew in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and man." (cf. 2:40 and 1 Samuel 2:26).

Two points in Luke's story deserve mention. First, he reminds us that Jesus was a normal child who experienced genuine human development — physically, mentally, emotionally, morally, and spiritually. This genuine humanity and unremarkable boyhood are precisely what the fanciful "infancy narratives" obscure and deny. But there's no need to fill in the blanks. We should be satisfied with the silence.

Secondly, Luke foreshadows the growing tension between Jesus's filial identity with God the Father — his emerging messianic consciousness, and his willing obedience to his earthly parents as a youngster. In the 15th century painting from Krakow that I have included, a sword pierces Mary's heart, as was prophesied by Simeon in Luke 2:35.

Eventually, Jesus's childhood obedience and unremarkable boyhood gave way to a radical disruption. By the time of his baptism by John in the Jordan River, and the beginning of his public ministry at the age of thirty, his family tried to apprehend him, his own siblings didn't believe in him, and the entire village of Nazareth tried to kill him as a deranged crackpot (cf. Mark 3:21, Luke 4:29, John 7:5).

But that's all. These two points do nothing to fill the thirty years of silence about the lost years of Jesus. I like to imagine that his early life was so insignificant, so prosaic, and so secluded in obscure Nazareth that there was nothing relevant to report. I also like to think that this silence speaks volumes to us today.

|

|

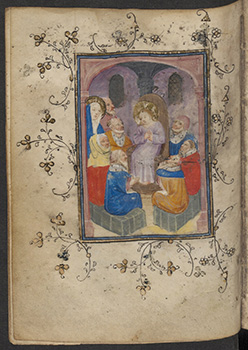

Illumination in a Book of Hours by Dutch Master of Zweder van Culemborg, c. 1420–1440.

|

If we embrace the silent years of Jesus instead of embellishing them with some ostensibly deep meaning, they subvert our media-saturated world of celebrity culture, influencers, overexposure, self-promotion, and endless noise. His hidden years suggest a counter-cultural spirituality of invisibility, obscurity, and even secrecy.

For many people today, and Christians are no exception, personal identity and fulfillment depend upon being well-known not unknown, visible and not invisible, honored rather than ignored, important instead of insignificant, and in demand rather than out of commission. But when I consider how utterly invisible Jesus was for 90% of his life, leaving no trace of who he was or what he did for thirty years, I'm attracted to a spirituality of hiddenness.

Most of us live hidden and unheralded lives by default. We live, die, and then will be forgotten to history. Ecclesiastes compares our little lives to an evaporating mist. Psalm 90 laments the futility of our transience. We will be lucky if even our grandchildren remember us. My friend Betsy is a stay-at-home mom who left a career as an attorney in order to cook, clean, do laundry, and chauffeur five kids to the dentist, school, birthday parties and sporting events. Claudette raised a family but now lives alone in a tiny apartment as an elderly widow.

Other believers have chosen hiddenness. The fourth-century monastics fled the corruptions of the crowded cities to seek Jesus in the vast solitude of the Egyptian desert. The Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1915–1968) spent twenty-seven years cloistered in Gethsemane Monastery in Kentucky, but nevertheless spoke to the entire world with his prophetic writings. In his memoir The Road to Daybreak, Henri Nouwen (1932–1996) describes why he left his professorship at Harvard to live and pray among the developmentally-disabled. When I visited Liberia in 2006 I was reminded how entire countries remain invisible to the world because they are so insignificant to the geo-political calculus of the day.

For Christians, the marvelous paradox is that the missing years of Jesus, no matter how completely lost to history, were not lost or hidden to God. Nor is my life or your life. Gaza, Ukraine, Syria, and Darfur are not hidden to God. After raising six kids and then experiencing a divorce and twenty years of clinical depression, my mother lived by herself for thirty-three years, but none of those years were lost to God.

|

|

Simon Bening, The Dispute in the Temple, c. 1525–1530.

|

Nothing at all is lost to God, because nothing at all can separate us from his love. Everything is known, loved, held, and protected by his providential care.

When Hagar the slave was banished to the emptiness of the desert, she nonetheless called Yahweh "the God who sees me." Her child bore a special name, Ishmael, which in Hebrew means "God hears" (Genesis 16:1–6). God sees and hears. He loves and cares. He doesn't ask us to lament or transcend our invisibility to the world. Our normal is the sacred.

The apostle Paul writes that our true life is "hidden with Christ in God" (Colossians 3:3). He described himself as "known, yet regarded as unknown" (2 Corinthians 6:9). In the Beatitudes, Jesus calls us to give, to pray, and to fast "in secret" (Matthew 6:4, 6, 18). The unseen Father who himself "is in secret," says Jesus, "sees in secret" what is done.

However hidden and obscure our little lives might feel, either literally or figuratively, whether voluntary or involuntary, in that very hiddenness God is present, just as He was with a twelve-year-old boy in an obscure Palestinian village.

For further reflection

Boris Pasternak (1890–1960)

Creation calls for self-surrender,

Not loud noise and cheap success.

Life must be lived without false face,

Lived so that in the final count

We draw unto ourselves love from space.

So plunge yourself into obscurity

And conceal there your tracks.

But be alive, alive your full share,

Alive until the end.

Weekly Prayer for Christmas

Denise Levertov (1923–1997)

On the Mystery of the Incarnation

It's when we face for a moment

the worst our kind can do, and shudder to know

the taint in our own selves, that awe

cracks the mind's shell and enters the heart:

not to a flower, not to a dolphin,

to no innocent form

but to this creature vainly sure

it and no other is god-like, God

(out of compassion for our ugly

failure to evolve) entrusts,

as guest, as brother,

the Word.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) Wikipedia.org.