From Our Archives

Ricardo Avila, Pentecostal Praise (2022); Debie Thomas, The One and the Many (2019); Debie Thomas, Words on Fire (2016); Edwina Gateley, Back from the Dead (2013); Kathryn Greene-McCreight, Pentecost: What It Is, What It's Not (2010); and Dan Clendenin, Beyond Babel (2007).

This Week's Essay

Genesis 11:1, “Now the whole earth used the same language and the same words.”

For Sunday June 8, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 104:24–34, 35b

Romans 8:14–17 or Acts 2:1–21

John 14:8–17, (25–27)

It’s hard to think about all humankind sharing one language without thinking about AI: this suddenly ubiquitous tool that lets a limited and fallible human mind pursue information in almost unlimited languages in a single instance and allows us access to all the Internet’s vast knowledge by just asking a question that doesn’t even need to be grammatically correct.

The other day I asked an AI chatbot a simple question about a particular place and time, and it confidently, with speed, gave me the wrong answer. I asked again, phrasing the question differently, and I got a different answer, also wrong. It just so happened that I knew these answers were wrong. I know I am not the only one counting the number of ways this confident ignorance could lead us astray.

As the author of this passage in Genesis knows, it isn’t just what happens when the answer is wrong. It’s also a problem of the process by which knowledge is acquired. In the first line of Genesis 11, the author makes a curious emphasis. “Now the whole earth used the same language and the same words” (11:1).

Why both language and words? Isn’t the same language necessarily comprised of the same words? The author seems astutely aware that people can speak the same language and still not use the same words, or that people can use the same words and mean completely different things. The problem doesn’t seem to be the social harmony that allows these people to build a tower and a city, but the arrogance that their easy understanding of each other has created.

|

|

“The Tower of Babel” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525–1569).

|

In many interpretations of this text, the destruction of the Tower of Babel stems from the builders’ exaggerated sense of their own power. They are thinking too big: a tower to the sky. Their arrogance and their certainty make them imagine a “name for themselves.” But in Aviva Zornberg’s book The Beginning of Desire: Reflections on Genesis, the midrashic scholar suggests that it’s not that the builders’ imaginations are too big, but that they are actually too small.

What the builders of the Tower of Babel fail to imagine, Zornberg writes, is “a multiplicity of selves, of worlds, existing together, even interacting with one another.” The Tower of Babel is a tower built on sameness, on conformity, on a denial of difference.

On the surface, the text seems to present a jealous and spiteful God who is against human achievement, a God who worries that humans will become too powerful and self-assured. I can imagine that the builders felt angry and lost when they watched their creation crumble to the ground: God must hate us. But the text introduces something more of a question: what is it about human purpose and cooperation that can go so wrong?

In Nobel Prize-winning author Olga Tokarczuk’s Polish-language novel Flights, the narrator, who spends most of the novel in airports, marvels at the fact that there are whole countries where people speak only English.

But not like us — we have our own languages hidden in our carry-on luggage, in our cosmetics bags, only ever using English when we travel, and then only in foreign countries, to foreign people. It’s hard to imagine, but English is their real language! Oftentimes their only language. They don’t have anything to fall back on or to turn to in moments of doubt.

|

|

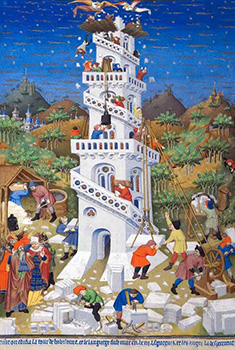

“The Bedford Hours,” Folio 17v (c. 1410–30). This work (artist unknown) was commissioned to mark the wedding of Anne of Burgundy and John, Duke of Bedford.

|

The narrator imagines all the languages of the world as private gifts given to individual peoples, except for English. When you have your own language, you have a sweet privacy that can be savored, an alternative logic that can be drawn on in difficult times. She pities those who have only English — that great global trade creole — as their only language.

How lost they must feel in the world, where all instructions, all the lyrics of all the stupidest possible songs, all the menus, all the excruciating pamphlets and brochures — are in their private language. They may be understood by anyone at any moment, whenever they open their mouths. They must have to write things down in special codes.

And then in a moment of surprising compassion for these English-only speakers, she imagines that someone, somewhere is going to give them a language of their own.

I heard there are plans in the works to get them some little language of their own, one of those dead ones no one is using anyway, just so that for once they can have something just for themselves.

Perhaps it was English-only speakers — trapped nervously inside a single public language — who persuaded the Trump administration to declare English the “official” language of the United States on March 1, 2025. It felt like a Tower of Babel moment, given the 350 other languages spoken in this country and the 300 more indigenous languages that were spoken here when the Europeans arrived. Perhaps Tokarczuk’s narrator would wish them “some little language of their own” so that they could learn the beauty of difference, the need to reach across boundaries for a more expansive imagination.

In the Qur’an there is a surah that is often cited by people in interfaith circles. It says, “We made you into peoples and tribes so that you might know one another.” This is a paradoxical statement. Isn’t it easier to know people who speak your own language and come from your own tribe? Why separate people by tribe and language if the end goal is knowledge? This is what the Tower of Babel builders knew to be true: it’s easier to build a tower if you all speak the same language.

And yet the knowledge that we acquire from reaching across boundaries is knowledge rooted in humility. It has in its memory all the clumsy mistakes we make as we try to cross that boundary: mistranslations, misunderstandings, even gestures that work one way in one culture and a completely different way in another.

|

But this is not an actual problem. This is a gift. Our bewilderment, the diversity of language and perspective, the fact that sometimes we use the same language but different words or the same words that mean different things — all of these are invitations to go deeper, invitations to welcome our own bafflement in the face of the reality of other human beings. One of the things that fascinates me about the story of Pentecost in Acts is that everyone keeps speaking their own language, but their understanding of each other is miraculously increased.

Zornberg points out that the story of the Tower of Babel is situated between two events of tremendous power in Genesis: the great flood and the call of Abraham. Just as the flood sets the stage for the tower, the tower sets the stage for the call of one lonely and nomadic man to take the first journey recorded in the Bible that isn’t compelled by exile or loss.

Because of this, I feel some hope for the people scattered after their failed tower-building experiment, forced to make a go of it in strange lands, speaking strange languages, trying to start over, rooted at last in their bewilderment. I feel hope because they’ve learned that there are forces at work that are larger than they are, that they cannot bend the world to their will. I feel hope because they must make a go of it from the ground up, through close listening, as Abraham does. It’s the opposite of AI: instead of announcing the wrong answer with confidence, we acknowledge our own ignorance, and use it as the ground to build on. This is a call we can all respond to, wherever we are.

Weekly Prayer

Orlando Ricardo Menes (b. 1958)

Praise be to God for confounding our tongues and scattering us into exile

like chaff in a stray wind or the fig seeds dropped by a green iguacaon on a hogplum.

Confusion is sweetest chirimoya on a dry tongue.

Hymns of disorder bring bountiful harvests in times of drought,

And perhaps only cross-eyes can see in chaos serene mandalas.

I shout from the top of my Babel’s tower sown as a kapok tree—

Blessed are the dialects, the patois, the argots, and the pidgins;

the half-breed word-hoards and the mongrel grammars; the geechees,

the calós, and the ghost words; those hallowed languages gone dead

or worse extinct because of genocide or conquest or just time’s erosion,

yet how we must mourn each one in our bones, hearts, spleens;

then join hands by the sea at dawn to chant their names in flames

of gumbo-limbo, O so many to remember: Elmolo, Mawa, Ba-Shu,

Koibal, Guanche, Calusa, Wichita, and the Taíno of my own island—

Kubanakán—whose words linger past the cyclones of our sadness

like flotsam chromosomes or castaway fossils of such beautiful amber

as barbacoa, canoa, fotuto, hamaca, iguana, malanga, tabaco, yuca.

With these words I make machines of memory in flesh and marrow.

With these words I glide and cleave the tidal waves of history.

With these words I take root in the quicksands of diaspora.Orlando Ricardo Menes (b. 1958) was born in Lima, Perú to Cuban parents and has lived in the United States since the age of ten. He teaches in the creative writing program at the University of Notre Dame. His most recent book is The Gospel of Wildflowers & Weeds (University of New Mexico Press, 2022), where this poem appears on p. 24.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) The Collector; and (3) Jean and Alexander Heard Divinity Library, Vanderbilt University.