From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, God's Gentle Whisper (2022); Debie Thomas, Legion (2019); and Dan Clendenin, Those Troublesome Christians (2016); My Name is Legion (2013); and Where is Your God? (2010).

This Week’s Essay

A guest essay by Barbara Pitkin (Ph.D. University of Chicago), Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies at Stanford University, and member of Grace Lutheran Church in Palo Alto, California. Barbara researches and writes about the history of Christian thought and biblical interpretation. Her most recent book is Calvin, the Bible, and History: Exegesis and Historical Reflection in the Era of Reform (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Galatians 3:27: “As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ."

Luke 8:35: “They found the man clothed and in his right mind.”

For Sunday June 22, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 42 and 43, or Psalm 22:19–28

Galatians 3:23–29

Luke 8:26–39

In U.S. society in recent years the term “inclusion” has undergone a political makeover. Now, midway through 2025, "inclusion" is at the center of polarizing ideological battles running through the country’s civic institutions, businesses and industries, religious bodies, and even households and families. Of course, questions surrounding practices of inclusion are not limited to the United States, nor are they by any means new. Across human history and all around the globe, communities large and small struggle to define who belongs and the criteria of fitting in.

Nearly two thousand years ago this was the very issue facing the new Christian community founded by the apostle Paul in Galatia. To be sure, questions surrounding identity and belonging were a natural part of the early Jesus movement’s evolution as it spread beyond its original Jewish context to embrace people from diverse cultural, class, and religious backgrounds. Roman society was a patriarchal and complex hierarchy shaping the lives of all those who lived in its vast empire. One’s legal rights, obligations, and treatment were determined by whether one was free or enslaved, citizen or non-citizen, privileged or poor, man or woman, adult or child. The first Christian missionaries had to address this status-conscious context.

To the extent that many of them, like Paul, were themselves Jews meant that divergent views on the importance of circumcision for Gentile converts to Judaism also informed how they approached the rules for inclusion for Gentile converts to the Christian gospel. Who could join up and belong, and what was required to do so? Did different rules for inclusion apply to people with different socio-economic status, religious heritage, or gender? Having encountered Christian missionaries who disagreed with Paul’s understanding of these matters, the Galatians were apparently concerned that what they had learned from Paul might not be correct.

|

|

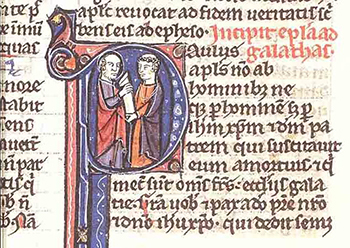

Illuminated manuscript of Galatians from the Bible of Borso d'Este (1425–1479).

|

In his rather testy response, Paul invokes his authority, or rather, the authority of the gospel he preached, received in a direct revelation from Christ himself (Gal. 1:11). Deepening this connection, he asserts further: “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2:20). He reminds the Galatians that they, too, have been transformed in their very being, metaphorically clothing themselves with Christ. Quoting an early Christian baptismal slogan, Paul proclaims a universal and inclusive view of Christian existence, transcending such external distinctions of gender, ethnicity, or religious heritage: “There is no longer Jew or Greek; there is no longer slave or free; there is no longer male and female, for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28).

Paul’s vision of a human nature restored in faith and baptism to unity harkens back to the original creation stories in Genesis, and especially to Genesis 1:26–27, to the first humans created in the image of God. To be sure, there are in verse 27 two types, male and female. Yet transcending this binary is the fact that the defining and distinctive feature of human nature is not gender but rather creation in the divine image. That this preeminent endowment was impaired by the Fall is an assumption practically universal in Christian theology; to what extent and the exact mechanisms for recovering it have been and continue to be the subjects of much theological debate. Paul’s metaphor of all becoming clothed with Christ represents his conviction that restoration involves renewal to the image of Christ, a new way of being, one that is open to all who believe, regardless.

And yet restoration of the divine image does not do away with all differences among humans, not among Christians and certainly not in the broader world they inhabit. This diversity is also part of human nature, but Paul’s argument is that such legitimate distinctions should not justify non-inclusivity and discrimination. It would be unproductive to list all the ways in which Christian institutions and individuals have shown exclusion and disunity. Because conformation to Christ’s image is a process, people will fall short of the goal of the inclusive orientation that Paul claims as part of renewal in Christ. But our progress is hindered when we excuse our shortcomings or rationalize that inclusion applies only in the spiritual and not the social realm. We need to confront our discomfort with our own fear over Paul’s challenging metaphor and the reality it represents.

Fear in the face of an inclusiveness that transforms individuals and upends social expectations and tidy hierarchies also emerges in the story from Luke about the healing of the Gerasene man possessed by demons. A man formerly from the city, where chains and shackles did not control him or his bizarre behavior, had been driven out. He was now living alone and naked among the tombs, apart from civilization. When those in town and beyond learn about Jesus’s exorcism, they flock to see. They find the man “sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed and in his right mind” (Luke 8:35). But instead of embracing him and welcoming him back to their midst, they are frightened. Seized with such great fear, in fact, that the whole throng asks Jesus to leave.

Had the Gerasenes reacted more inclusively, they might have been able to grasp that beyond his material clothing, here was a man now clothed with Christ. A man who becomes the first in Luke’s Gospel to bear the good news about Jesus to the Gentiles. But their initial reaction was not rejoicing over his transformation, nor reintegration into their society, but discomfort and fear in the face of the implications for themselves and their world of Jesus’s disruptive act.

The offer to clothe oneself with Christ is extended freely, with no strings attached, and grasped by all who receive it through sheer grace. But the life to which they are called entails costs. Christ is not merely draped over us like an outer covering but also knit into the fabric of our very being. We, like Paul, no longer live, but Christ lives in us.

|

|

Paul gives his epistle to a Galatian, National Library of the Netherlands (France, 1300–1500).

|

If Christ lives in us, then Christ also loves in us and through us. But like the Gerasenes, when we are confronted with Christ’s transformative grace and the new, inclusive realities to which we are called because of our faith, we often draw back, in discomfort and fear. How can we move beyond the temptation to ask Jesus to leave and instead invite him to wrap himself more tightly and weave his love into the material of our hearts? To become not only Christ’s living image but also his loving image?

In her poem “The Star Market,” Marie Howe explores the challenge of embodying this inclusive love, detailing the discomfort of encountering “the people who Jesus loved” while shopping for groceries. The poet can “hardly look at them,” but concrete and vivid imagery awakens the reader’s senses as we see, hear, and smell the man at the checkout and the other people in the store and parking lot. The boundaries dividing poet from “the people Jesus loved” at the start of the poem (“I had to step back a few steps”) begin to blur. The poet also “wanders” through the store and “stumbles” her way through the parking lot. Is she really all that different?

The reader also is included in this powerful meditation. First as an external observer, and then through a transcending of the differences among poet, a biblical woman healed by Jesus, and the reader in the last two lines. “If I touch only the hem of his garment, one woman thought, I will be healed.” The healing of the woman with the bleeding issue follows immediately from the healing of the Gerasene man in Luke’s account (Luke 8:43–48). How intriguing that she references Jesus’s clothing as the site of access to his transformative and healing power. We are taken back to Paul’s image of being clothed with Christ and to the Gerasene man, clothed and healed. But who is the speaker of the poem’s final line? Is it the biblical woman suffering chronic bleeding? Or is it the speaker the poet, or the reader? Or all three?

If I touch the hem of his garment, will my response, like that of the Gerasenes, be one of fear? Or will I be able to bear the look of his face? Indeed, to bear it in the sense that Paul enjoins: to be renewed according to his image and, so clothed with Christ, advance the inclusive welcome that sees all as people Jesus loves, regardless?

Weekly Prayer

By Marie Howe

The people Jesus loved were shopping at The Star Market yesterday.

An old lead-colored man standing next to me at the checkout

breathed so heavily I had to step back a few steps.Even after his bags were packed he still stood, breathing hard and

hawking into his hand. The feeble, the lame, I could hardly look at them:

shuffling through the aisles, they smelled of decay, as if The Star Markethad declared a day off for the able-bodied, and I had wandered in

with the rest of them: sour milk, bad meat:

looking for cereal and spring water.Jesus must have been a saint, I said to myself, looking for my lost car

in the parking lot later, stumbling among the people who would have

been lowered into rooms by ropes, who would have creptout of caves or crawled from the corners of public baths on their hands

and knees begging for Mercy.If I touch only the hem of his garment, one woman thought, I will be healed.

Could I bear the look on his face when he wheels around?From The Kingdom of Ordinary Time: Poems (W. W. Norton & Company, 2009). Marie Howe (born 1950) is an American poet, a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and Poet-in-Residence at The Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Meisterdrucke Kunstreproduktionen and (2) Wikimedia.org.