From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week’s RCL texts, see Sara Miles, Like Lambs Among Wolves (2007); Dan Clendenin, Believers Without Borders (2010) and Go! Jesus Sends the Seventy-Two (2013); Debie Thomas, Choosing What is Easy (2019); and Dan Clendenin, Exclusion and Embrace (2022).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Psalm 30:5: "Weeping may linger for the night, but joy comes with the morning."

For Sunday July 6, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 30 or Psalm 66:1–9

Galatians 6:1–6, 7–16

Luke 10:1–11, 16–20

In Walker Percy’s 1961 novel The Moviegoer, the narrator Binx is a young, disillusioned, southern white man working for a brokerage firm and trying to avoid the question of what to do with his life. He seeks the provisional comforts of movie-going and zipping around in his MG, even though he claims to dislike cars.

Binx is an entitled and self-absorbed man who is about to turn thirty. He says things like, “What satisfaction I take in appearing the first day to get my car tag and brake sticker!” It’s a little tongue-in-cheek, and hiding underneath Binx’s sarcastic veneer is a condition that he calls “despair.”

What makes Binx worth the reader’s time is his eloquence about both his spiritual emptiness and the subsequent search it sends him on.

“The search,” he says, “is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” He can’t name the object of his search. He says that’s because of his “fear of exposing [his] own ignorance.” But there is also a hint of competitiveness. If almost all Americans have already made up their minds about whether or not God exists, he says, then he doesn’t want to be “dead last” in making up his own mind.

|

|

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, by Andreas Heidrich.

|

Yet he also poses the question, “Have 98% of all Americans already found what I seek or are they so sunk in everydayness that not even the possibility of a search has occurred to them?” Binx’s willingness to undertake the search in 1961 New Orleans is what makes The Moviegoer one of my favorite novels.

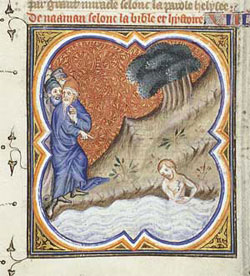

In Second Kings, we read about Naaman, a 4th century BCE figure from the kingdom of Aram. Naaman is clearly an entitled man with a big ego who thinks that kings should act on his behalf. Yet he is also suffering. He has a contagious skin disease that means his suffering is not only physical, it is also social. Even though he is a commander, a revered military figure, no one wants to be near him.

In The Universal Christ, Richard Rohr writes that there are really only two things that compel us toward spiritual growth: love and suffering. These are the primary tools of our transformation. And transformation is not found in self-development or self-improvement, but in unlearning and undoing, in letting go and surrendering. Typically we don’t have to look too hard for what to let go of. As Paula D’Arcy puts it, “God comes to you disguised as your life.”

For Naaman, it is suffering that propels him into what Binx might call “the search.” As he attempts to find freedom from his suffering, he is led on a path of spiritual growth. What’s redeeming for me about this arrogant man is his willingness to go on that search.

|

|

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, 12th century Germany.

|

I wonder what it took for him to hear at last the voice of the slave girl, herself a symbol of his own power and victory. What pain would have been required for him to listen? All the voices of healing in this story come from people that Naaman no doubt thought beneath him.

Naaman keeps searching; he keeps looking. And he keeps getting in his own way. There is something endearing about his blustery attempts to find healing and then his rejection of what’s offered to him. First he wants power, connections, and wealth to give him relief; then he seeks acknowledgment; and finally he wonders if he could simply heal himself in the waters of his own rivers. Why would he have to go to the Jordan? He’s prickly, easily offended, and inclined to abandon the search because he doesn’t like its terms.

This story would be less intriguing if Naaman had simply said, “Sure. Take me to the Jordan. I’ll give it a go.” What makes it relatable is how long it takes, and Naaman’s resistance. What makes it painful is how Naaman extends his own suffering even as it leads him step by step.

Naaman’s servants clearly understand him and his ego. They say to him, “If the prophet had asked you for something hard you would have done it.” Apparently Naaman liked to do hard things, like fight battles. But here is something easy that’s asked of him. It’s an inversion of the classic fairy tale scenario where the hero must undertake an impossible task: count all the grains of sand on the sea shore or separate every grain of poppy seed from every grain of millet. But Naaman is no hero, and his task is far simpler. He’s just a man in pain.

The passage is psychologically astute in noting the kinds of objections to healing that we come up with. We think other people are minimizing our pain or refusing to listen. We want others to notice us, and we think the greater their attention the likelier our chances of healing. We want to control the who and the how, the when and the where of our own healing.

But grace works despite our best efforts to avoid it. The waters of the Jordan — whatever you may think of them — are still there waiting for us.

|

|

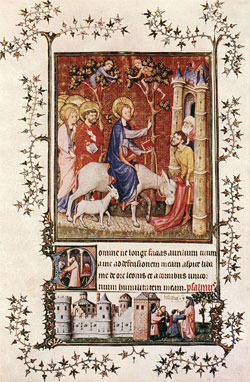

The Cleansing of Naaman by the Prophet Elisha, Master of the Baptist, c. 1409.

|

Once you’ve acknowledged that there is a search, Binx notes that it does no good to stand outside the world and explain things to yourself. The idea of the Jordan will get you nowhere. You can explain the search all you want in your head — reasonably, perfectly, with a strong sense of your own correctness. You can tell anyone who will listen why your God is the right God and your power is the right power and your rivers are better than anybody else’s rivers.

But then you arrive again at the problem of yourself and your pain. “Though the universe had been disposed of,” Binx says, “I myself was left over.”

On the search, you begin to hear the still, small voices: Go, ask, wash. You begin to attune, and the world begins to speak back to you. And as you learn to follow, your own failures and mistakes and ego-driven refusals are used as fodder to lead you deeper.

The story has a happy ending — Naaman is restored! And he seems to understand something new about this miracle: he asks to carry back earth from Israel, perhaps so that he can remember how he was healed in spite of his prejudices and his certainties and his power-mongering.

But as folklorist Clarissa Pinkola Estés says, “Though fairy tales end after ten pages, our lives do not. We are multi-volume sets…. There are always more opportunities to get it right.” The search goes on.

At the end of The Moviegoer, Binx turns back with new eyes toward the everydayness for which he has had so much contempt. He says, “There is only one thing I can do: listen to people, see how they stick themselves into the world, hand them along a ways in their dark journey and be handed along, and for good and selfish reasons.”

Weekly Prayer

Edwina Gateley (b. 1943)

Called to Say Yes

We are called to say yes.

That the kingdom might break through

To renew and to transform

Our dark and groping world.We stutter and we stammer

To the lone God who calls

And pleads a New Jerusalem

In the bloodied Sinai Straights.We are called to say yes

That honeysuckle may twine

And twist its smelling leaves

Over the graves of nuclear arms.We are called to say yes

That children might play

On the soil of Vietnam where the tanks

Belched blood and death.We are called to say yes

That black may sing with white

And pledge peace and healing

For the hatred of the past.We are called to say yes

So that nations might gather

And dance one great movement

For the joy of humankind.We are called to say yes

So that rich and poor embrace

And become equal in their poverty

Through the silent tears that fall.We are called to say yes

That the whisper of our God

Might be heard through our sirens

And the screams of our bombs.We are called to say yes

To a God who still holds fast

To the vision of the Kingdom

For a trembling world of pain.We are called to say yes

To this God who reaches out

And asks us to share

His crazy dream of love.Edwina Gateley is an English poet, teacher, mystic, and activist who founded a hospitality house for women who had been involved in prostitution in Chicago. This poem comes from her book There Was No Path, So I Trod One (Source Books, 2013).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) MediaNet2002.de; (2) © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence; and (3) The Web Gallery of Art.