For Sunday May 29, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

1 Kings 18:20–39 or 1 Kings 8:22–23, 41–43

Psalm 96

Galatians 1:1–12

Luke 7:1–10

If you held a contest for "Most Offensive Passage in the Bible," the readings for this week offer not one but two strong candidates.

1 Kings 18 tells the story of Elijah's mass murder of the 450 prophets of Baal. This "text of terror" raises honest questions about important matters — especially those about religious pluralism and sacred violence. I wrote about this story in an earlier essay.

In this essay, I'm interested in the second candidate — Paul's fiery rhetoric to the Galatians. He writes:

"I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you to live in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel — which is really no gospel at all. Evidently some people are throwing you into confusion and are trying to pervert the gospel of Christ. But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel other than the one we preached to you, let them be under God’s curse! As we have already said, so now I say again: If anybody is preaching to you a gospel other than what you accepted, let them be under God’s curse!"

In the book of Acts, Peter preached that "there's no other name." Here in Galatians, Paul writes that "there's no other gospel."

The earliest believers acknowledged that Jesus was a prophet without honor and a crucified criminal. He's a rock that makes us stumble, a stone rejected by builders. To the Jews he's a scandal and to Greeks he's foolishness. Paul tells the Galatians that if he wanted to earn human approval, he sure wouldn't be preaching Jesus.

But exactly what was so offensive about Paul's gospel? And, conversely, what was the "different gospel," the "no gospel at all," and the "other gospel" that Paul calls a perversion and confusion of his message? What, precisely, did Paul anathematize? What was he defending and denying?

For the church at Galatia, the answer to these questions is simple, clear, and shocking.

|

|

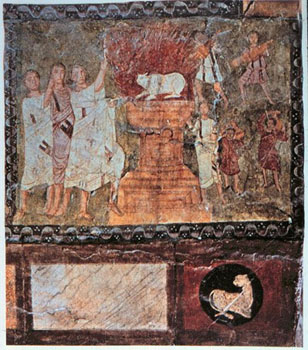

Elijah on Mt. Carmel, Dura Europos synagogue, c. 245 CE.

|

In Galatians, Paul addresses a very specific question: must Gentile converts follow the Jewish law?

This question was also the subject of Peter's dramatic conversion in Acts 10–11, where he learned that "God does not show favoritism" but welcomes all people equally — even a Gentile like Cornelius. This inclusive and expansive message subverted all that a conscientious Jew like Peter held dear out of his sense of fidelity to God.

After his "Cornelius conversion" that repudiated all forms of exclusion, Peter the Jew ate with the unclean Gentiles. But in Galatians we learn that he later regressed into gross hypocrisy.

Paul says that "certain men came from James" — that is, Jewish leaders of the Jerusalem church, teaching that Gentile converts had to obey the Jewish law. Peter succumbed to their demands and "began to separate himself from the Gentiles." There was also a domino effect when other believers followed Peter's hypocrisy, even the beloved Barnabas.

Paul used the harshest language to repudiate those who had narrowed the gospel down to a Jewish sect. His gospel was about expanding the message to include Gentiles and all the world. And so, "when Peter came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face." "We didn't give in for a moment."

This is why Paul said that in serving God he didn't seek human approval. If you want human approval, you privilege your own In group over every Other group. You limit God's love to your own tribe, and claim to be the sole inheritor of the divine promise. But when you insist that God loves people who are outside of your in group just like they are — and the "dirty" Gentiles were, by definition, "unclean" for ritually pure Jews, then you incur human wrath, for you've betrayed the cause and transgressed the carefully drawn boundaries.

It took a while, and even today we relapse into hypocrisy like Peter, but Paul eventually won this argument. Henceforth, no longer would the good news of God's love be limited to an exclusive few. Rather, it became an inclusive message for all the world, and so, instead of remaining a Jewish sect, "Christianity" became a global religion.

The "perverted gospel" that Paul anathematizes in Galatians is one that restricts, narrows, or limits the love of God to an exclusive few — in his time and place, those believers who wanted to force Gentiles to live like Jews.

The "true gospel" that Paul defends is one that expands the love of God in Christ to all people without exception and subverts our spiritual hierarchies. In Galatians, Paul says that his gospel bursts our normal boundaries of exclusion, like race, religion, gender, and class — "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ."

|

|

Elijah and the prophets of Baal, England, woodcut, 1539.

|

Through the one particular man Jesus, the love of God embraces all the world. As Karen Armstrong observes in her new book St. Paul (2015), for many people Paul has been "the apostle we love to hate," as if by our modern sensibilities he's a horrible bigot. But in fact, we see his universal expansion of the gospel to all the world, and even the entire cosmos, over and over again in his epistles.

Paul compares the "first man" Adam with the "last man" Jesus in Romans 5. Just as sin, death, and suffering came to all humanity through the one man Adam, "how much more did God's grace and the gift that came by the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ, overflow to the many!" Just as Adam's one trespass brought condemnation to us all, the one act of righteousness by Jesus Christ "brings life for all people."

When God chose Abraham to form one, particular nation, his election of Israel did not mean his exclusion of Gentiles. In fact, quite the opposite. God said that he would bless not only Abraham's progeny, but "all peoples on earth" (Genesis 12:3, 22:18).

When God repeated his covenant with Isaac, he reiterated his intentions for all the world: "in you, Isaac, all nations on earth will be blessed." (Genesis 26:5). And when Isaac's son Jacob used a rock for a pillow and dreamed a dream at Bethel, God repeated verbatim: "In you, Jacob, all peoples on earth will be blessed." (28:14).

Psalm 96 for this week addresses not just the one nation Israel, but "all the earth," "all peoples," all the "families of nations," the entire creation, "and all that is in it" — the heavens, the earth, the sea, the fields, and the trees.

In Luke 7 for this week, Jesus says that a Roman solider had a more authentic faith than a ritually clean Jew.

Every person is created by God. Each one of us bears his image. We all belong to one human family. We all breathe the same air and drink the same water. Every person, says Paul, is God's "offspring" (Acts 17:28).

In Ephesians, Paul makes a clever phonetic play on words to emphasize this point. He says that God is the patera of every patria—the "father (patera) from whom every family (patria) derives its name" (1:14–15).

|

|

Elijah and the prophets of Baal, painted porcelain tile, 1699, Syria.

|

God isn't the God of Jews alone, or the private possession of Christians. He isn't America's god. Rather — and here the translators struggle, he's the "father of all fatherhood," the "father of every family," and the "father of the whole human family." He's the God of Muslims, Buddhists, and atheists. Paul even expands God's fatherly favor to the unseen world of "every family in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 3:14–15).

For Paul, there's a universal logic to the Christian story. God "created all things in heaven and on earth" (Colossians 1:16). He seeks the worship of all "things in heaven, and things on earth, and things under the earth" (Philippians 2:9–11). He will "reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven" (Colossians 1:20), and he will sum up or bring together "all things in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 1:10).

For John, Jesus is the atoning sacrifice not just for a privileged few but "for the entire cosmos" (1 John 2:2).

And so, the ultimate destiny of all creation is liberation and freedom, adoption and redemption. The scale and scope of this future hope includes not only each person and every nation, but "the whole creation" (Romans 8:12–25). Peter calls it the "universal restoration of all things" (Acts 3:21).

Anything less is the perversion of restriction and exclusion. Paul anathematizes such limits on the love of God as "a different gospel."

Image credits: (1) Blogspot.com; (2) Harvard Art Museums; and (3) Blogspot.com.