Film Reviews

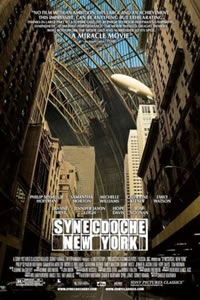

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

The question for this complex and weird film is whether writer-director Charlie Kaufman's artistic ambition will ultimately frustrate viewer patience. When I saw the film, a couple in front of me walked out halfway through. You will probably love or hate this film; reviews have been sharply divided.

Philip Seymour Hoffman stars as Caden Cotard, a theater director mired in all the midlife crises, real and imagined, of body, mind and spirit. The film begins conventionally enough, or so it seems, but there are telltale signs early-on that Kaufman is going to play with reality itself — a cartoon on the family TV features Caden as a character, and a realtor walks a client through a house that is permanently on fire. Those are two ominous metaphors.

The giveway is that the name "Cotard" bears a striking resemblance to that of the French postmodernist Jean-Francois Lyotard. We shouldn't be surprised when Caden quits his career doing theater among the "blue hairs" in suburban Schenectady, New York, where his latest production was "Death of a Salesman," and with the help of a MacArthur genius grant (a cruel irony given his circumstances) moves to a cavernous warehouse in New York City and recreates his confused life through what eventually becomes a cast of hundreds of characters. Yes, life is a stage and we're the actors.

In his book The Post-Modern Condition (1979), Lyotard made (in)famous the notion of "incredulity toward meta-narrrative," a fancy way of saying that there are no truly universal or absolute meanings or truths in life, and that all meaning is a personal or social construction. This is exactly what Caden tries to do — he creates meaning in his life through characters who portray his life. He keeps changing the name of the play, one of which is "Simulacrum" (= an insubstantial semblance of something). He keeps saying that he "finally" knows how he wants to direct the play. Indeed, the play is never finished but is instead a building project that piles floor upon floor of sets; it never ends. For Kaufman there's a very thin line between authenticity and absurdity, genuine reality and mere representation, fact and fiction, living life and playing roles, healthy self-awareness (however painful) and oppressive self-consciousness, and between true life and certain death.

Does Caden's effort to manufacture even the barest micro-meaning make any sense? The last line of the movie offers a glimmer of hope. Maybe.