Book Notes

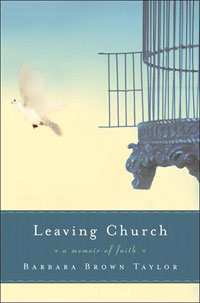

Barbara Brown Taylor, Leaving Church; A Memoir of Faith (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 235pp.

Barbara Brown Taylor, Leaving Church; A Memoir of Faith (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 235pp.

Most Christians devoted to parish ministry like Barbara Brown Taylor discover at some point in their lives the perilous interface between one's personal identity and the professional institution of the church which they serve. Often this interface brings a deep sense of satisfaction and fulfillment, but at other times it becomes a flash point for crisis. In the words of the Benedictine nun Joan Chittister, given the grace of experiencing the faults and failures of both myself and the church, how do I remain a "loyal member of a dysfunctional family?"

After ministering for nine years on the staff of a large Episcopal church in urban Atlanta, where she had lived half of her adult life, Taylor moved to Clarkesville in northeast Georgia, a town of 1,500 people and two stoplights. The prospect of serving Grace-Calvary Episcopal with its tiny sanctuary that seated 85 people was a dream come true for her, or so she thought. Her passion and competence spelled success, and after five years the church had expanded to four Sunday services. In the process she nearly lost her soul, and so she resigned, left church, and took an endowed chair of religion at nearby Piedmont College.

Taylor's memoir reads like an account of classic burnout—an exaggerated sense of self-importance, her "staggering" sense of ownership, a deep need to help others, a relentless work ethic, self-pity, a "heroic image of myself [and] a huge appetite for approval." All these led to a meltdown of bitterness, loneliness, uncontrollable tears, and resentment. "My role and my soul were eating each other alive," she writes. In addition to describing her personal issues that contributed to her crisis, Taylor also reflects on the church as an institution. Here too we discover familiar if frustrating experiences. While Jesus prayed for a kingdom of God, what we got was an imperfect church. The church guards its "center" and often persecutes those on the "edges." Rigid belief enforced by "jurists" marginalizes the "poets" who would rather "behold."

Taylor structures her narrative around the themes of finding, losing, and keeping. She discovered that what she really wanted was to become merely but fully human. She lost her parish job but gained Sabbath rest. She lost her professional identity but gained a far broader and deeper identification with all of humanity. Most important of all, she discovered a spirituality of imperfection in which "spiritual poverty is central to the Christ path." As this is what she calls a "love story" and a "memoir of faith," her candid narrative reminded me of the wise words of Erasmus who, after failing at rapprochement with Luther, returned to the Catholic church with all its imperfections. "I will put up with this church until it becomes a better church," said Erasmus, "and it must put up with me until I become a better person."