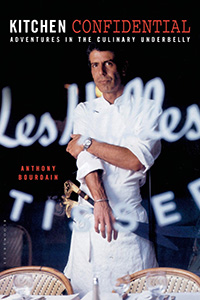

Anthony Bourdain, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 312pp.

Anthony Bourdain, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 312pp.

I'm way late to this iconic memoir, but perhaps there are some advantages to reading a bestseller that was published twenty-two years ago. At least I'm not alone — our public library has fourteen copies of Kitchen Confidential, and half of them are checked out. I suspect people are still reading the book because of Bourdain's tragic death in 2018, the newly released documentary movie about him called Roadrunner (2021), but mainly because of the enduring value of the book itself: it has stood the test of time.

Bourdain never intended to write an "expose" about the underbelly of a renegade subculture, but that's how most people read his book. It led to his "unexpected notoriety" (not to mention further successes) as "the poster boy for bad behavior in the kitchen." The stories are now standard fare, but back then they were shocking. High end restaurants recycle uneaten bread. Don't order fish on Monday. Weekend brunches are a dumping ground for expiring leftovers. Sex, drugs, misogyny and chaos characterize restaurant kitchens, and for a long time all that was glamorized.

What Bourdain wanted to write was a book for his fellow professional cooks, in their unique jargon of "kitchenese." He aimed for brutal honesty and authenticity, and struck gold. His fellow foodies absolutely loved it. "Dude, you wrote my life!" was a compliment he received many times from all over the world. One of the main themes of Kitchen Confidential is this comraderie among the waiters, cooks, dish washers, expediters, sous chefs, line cooks, etc. "I love the sheer weirdness of the kitchen life," he writes — "the dreamers, the crackpots, the refugees and the sociopaths with whom I continue to work. The professional kitchen is the last refuge of the misfit. It's a place for people with bad pasts to find a new family." Bourdain was also one of the first chefs of his caliber to give long overdue credit to the Latino community as the "backbone" of the restaurant industry.

Given Bourdain's suicide in 2018, it's impossible to read his memoir without a sense of foreboding and tragedy. We shouldn't glamorize the brutality and vulgarity of what he describes, a point made by the chef David Chang in his new memoir Eat a Peach. Bourdain admits to having left "a lot of destruction in my wake." He articulates the shame, guilt, fears and regrets that he piled up. He describes his heavy drug abuse that included heroin and cocaine, his self-loathing, and "how far I'd fallen." On the last page he says that it's telling that he was most relaxed when he was all alone in an airport smoking lounge with a drink and a cigarette, jetting from one marvelous destination to another: "I'm free, as it were, of the complications of normal human entanglements, untormented by the beauty, complexity and challenge of a big, magnificent and often painful world." And then the last sentence of the book: "Human behavior remains a mystery to me."

Lord, give to the departed eternal rest.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net