Book Notes

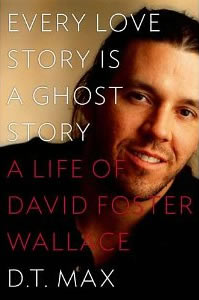

D.T. Max, Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story; A Life of David Foster Wallace (New York: Viking, 2012), 356pp.

D.T. Max, Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story; A Life of David Foster Wallace (New York: Viking, 2012), 356pp.

By the time David Foster Wallace graduated from Amherst College in 1985, he had won ten academic awards and written two senior theses. One was for the philosophy department on modal logic, the other a 500-page monster for the English department, which was published as his first novel when he was twenty-three (The Broom of the System). He had also developed a heavy drug habit, battled severe clinical depression, attempted suicide, and submitted himself to psychiatric hospitalization. In this first full-length biography of Wallace, these two themes crisscross like a double helix — a brilliant polymath who for many readers altered the form and function of writing fiction, and a tragic life that ended in suicide at the age of forty-six after struggling for thirty years with what he called The Bad Thing.

Wallace's early work was "obsessed" with the post-modern project and the literary theory of Wittgenstein, Derrida, and Gadamer. His later work broke decisively with this to explore a deeply practical question: what does it mean to live an authentic human life in contemporary society? Wallace argued that today we no longer esteem those who care, but those who affect not to care. Our elite trend setters are characterized by chronic irony, cynicism, a smugness that knows everything is cliched, hyped, empty, and absurd, and a desire to be seen as being aware. David Letterman or Stephen Colbert comes to mind.

But Wallace's life collided with his work. Irony is fine as a negative tool, but it offers no positive alternative and so is defeatist. The problem is exacerbated by virtually every important cultural trend — television, media overload, pornography (which combines false pleasure and marketing), music, fabricated amusements like cruises, etc. As a result, our passions are not our own; they've been altered and manipulated by the corrosive forces of pseudo-pleasure, consumption, drugs, distraction, self-absorption, and boredom. These ideas came together in Wallace's quirky, thousand-page novel Infinite Jest (1996), considered by some to be one of the most important works of avant-garde fiction in decades.

In the end, Wallace became what Max calls a "full-fledged apostle of sincerity." At his many AA meetings, he learned from recovering addicts that truth-telling had to be "maximally unironic," wary of pretension, evasion, and cleverness. The cliches of recovery thus supplant the technical jargon of literary theory. Sincerity replaced irony as a virtue, and "saying what you meant became a calling." Of course, this risks the condescension of the cultural ironists. At the end of his biography, Max makes a provocative comparison between Dostoevsky and Wallace (who was never religious): "Like 'the good old Brothers K,' as Wallace called Dostoevsky's novel, Infinite Jest counterposes sincerity and faith against moral lassitude. Both eschew stylish irony to make a simple point: faith matters" (288).

For a full-length review of Max's biography see Elaine Blair, "A New Brilliant Start," NYRB (December 6, 2012).