Book Notes

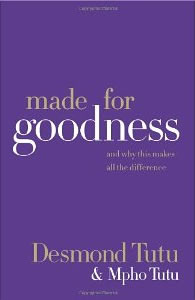

Desmond Tutu and Mpho Tutu, Made for Goodness, And Why This Makes All the Difference (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 206pp.

Desmond Tutu and Mpho Tutu, Made for Goodness, And Why This Makes All the Difference (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 206pp.

Growing up under South African apartheid, Desmond Tutu has experienced enough injustice, oppression and cruelty to embitter any normal person. But the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize (1984) and chair of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission refuses to succumb to anger or futility. In fact, in this book he proclaims a wonderfully positive message, that each and every person is fundamentally good. Goodness is the essence of what it means to be human, rooted as it is in the first few pages of the Bible where God declares six times that "all he made" is "good," and then a seventh time that it is all "very good" (Genesis 1:31).

Tutu doesn't deny the reality of sin, suffering and evil, "but they are not our essential nature. They are aberrations. What is normative is goodness. Wrongness runs against the grain of creation" (194). The liberating implications of this, he tries to show, are that we need not try to be good in order to earn God's love, but simply accept that we are accepted. In successive chapters Tutu considers why God allows evil and suffering, what it means to exercise free choice, the role of habit in forming our moral character, and the practices of repentance, prayer and silence.

Throughout the book Tutu draws upon the Xhosa word ubuntu, which means something like "tend and befriend." Ubuntu insists that we all need each other, that we can only be fully and truly human by acknowledging our interconnectedness. "My humanity is bound up with your humanity." In addition, Tutu makes liberal use of his personal experiences of apartheid. Nelson Mandela, for example, chose the path of reconciliation rather than wrath and rage. Although he writes from his specifically Christian vision as an Anglican priest, and returns numerous times to the parable of the prodigal son, there are only about a dozen references to Jesus. He's just as likely to invoke the Dalai Lama, the peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh, Ghandi, Muslim friends, and even Oprah. No doubt this is an effort to make the broadest possible appeal. A poem ends each chapter to provoke meditation and reflection. One oddity of the book's style was referring to his daughter and ostensible co-author always and only in the third person.