Book Notes

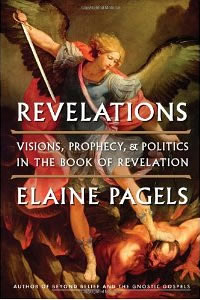

Elaine Pagels, Revelations; Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation (New York: Viking, 2012), 246pp.

Elaine Pagels, Revelations; Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation (New York: Viking, 2012), 246pp.

No book in the Bible has provoked more controversy, esoteric speculation, or misunderstanding than the very last one — Revelation. In the fourth century notable scholars like Chrysostom and Eusebius hesitated to include Revelation in the canon. Martin Luther described it as "neither apostolic nor prophetic. My spirit cannot accommodate itself to this book. I stick to the books which present Christ to me clearly and purely." John Calvin wrote commentaries on every book in the New Testament except Revelation. Among Eastern Orthodox believers Revelation is the only book not read in their public liturgy. As Elaine Pagels notes in her most recent popular book, Revelation "barely squeezed into the canon."

Pagels sees John of Patmos as a Jewish prophet in the tradition of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, all of whom wrote "war time literature." John's Revelation is a piece of "anti-Roman propaganda," writing as he was a few decades after Rome ransacked Jerusalem in 70 AD. Revelation is also a polemic against those whom John castigates as a "synagogue of satan" and "those who say they are Jews and are not." For Pagels "the synagogue of satan" are not actual Jews who were attacking "Christians," but rather Gentile converts of Paul who rejected Jewish distinctives like the Mosaic law (cf. Galatians).

What especially interests Pagels are the dozens of other revelations (plural) found in the apocryphal literature. She admits that these aren't apocalyptic texts like Revelation, or in many cases are they even Christian. Just ten years after intense persecution under Diocletian, Constantine converted and outlawed all competing sects and claims of revelation as heretical. Interpretations of the book of Revelation then flipped: no longer did readers see pagan persecutors as their enemies; rather, the whore of Babylon and the Beast were marginalized revelations that people like Athanasius wanted to suppress in the name of an orthodox agenda of "creed, clergy and canon" (169).

Pagels writes history with a purpose — to grant spiritual parity to these many revelations that were excluded from the canon as heretical. The last sentence of her book arrives at the destination that was never in doubt: "And unlike those who insist that they already have all the answers they'll ever need, these sources invite us to recognize our own truths, to find our own voice, and to seek revelation not only past, but ongoing." Fair enough, but you'll need other sources to help think about whether a revelation claim might be wrong and take you tragically far afield, or whether being wrong even matters. Why should one reject the claims of David Koresh but accept those of a Buddhist monk? Or vice versa? I can't imagine Pagels would endorse the idea, but she makes it sound like it's impossible to be wrong.