Book Notes

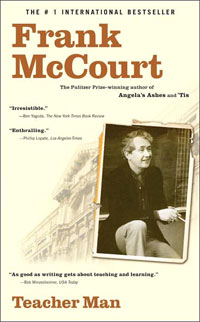

Frank McCourt, Teacher Man; A Memoir (New York: Scribner, 2005), 258pp.

Frank McCourt, Teacher Man; A Memoir (New York: Scribner, 2005), 258pp.

In 1996 at the age of sixty-six, Frank McCourt published his first book, Angela's Ashes, which told the story of his hardscrabble and deeply Catholic childhood in Ireland. He wrote the book for his family, he said, and hoped that it might sell a few hundred copies. "Instead," he recounts, "it jumped onto the bestseller list and was translated into thirty languages." In fact, Angela's Ashes won the Pulitzer Prize. Not bad for a man who taught high school English in New York City for thirty years. McCourt followed with a sequel called 'Tis (1999), which picked up his story in the year 1949 when his family returned to the United States after having moved back to Ireland when he was four years old. Now seventy-five, McCourt completes his trilogy with Teacher Man, a memoir about his thirty years as a public school teacher that began in 1958.

You almost believe him when McCourt insists that there was "nothing remarkable" about his thirty-year stint in five different public schools in New York City. His first job was at McKee Vocational and Technical School where virtually every kid was destined to work as a beautician, a mechanic, a dock worker, or the like. His last job found him at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan where parents expected their kids to attend Ivy League schools. Between these extremes it was McCourt's genius that nothing human, nothing at all, was ever alien to him. He did not romanticize the poor nor pander to the rich. He insists that he received far more than he gave.

McCourt is unsparing in his narrative of his rise from the "rock bottom of the social hierarchy." At one point he describes himself as a "failed everything." Even late in his teaching career, after his marriage collapsed and he failed in his two years at a PhD at Trinity College in Dublin, he lived in a small apartment above a bar. But he was dogged. Five classes every day, five days a week. Hormonal teenagers from across the ethnic rainbow, anxious parents, petty administrators, and mindless bureaucrats. His description of taking his ninth grade class of twenty-nine black girls and two Puerto Rican boys on a field trip to Times Square is worth the price of the book (pp. 136–146). He was also creative. He had his students read recipes from cookbooks and set the "lyrics" to music. When he recognized passion and creativity in all the forged permission slips he accumulated, he had his kids write "excuse notes" from Adam and Eve to God. We're not surprised that he won Teacher of the Year at Stuyvesant. With a Pulitzer for his first book readers have come to expect McCourt's masterful storytelling. Poignant memories, human pathos, self-effacing humor, and irreverent opinions grace these pages of a wonderfully ordinary and extremely gifted "teacher man."