Book Notes

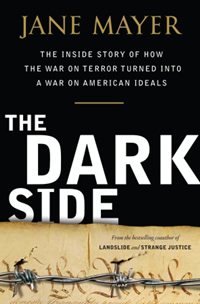

Jane Mayer, The Dark Side; The Inside Story of How The War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 392pp.

Jane Mayer, The Dark Side; The Inside Story of How The War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 392pp.

The first Sunday after the September 11 terrorist attacks, Dick Cheney appeared on Meet the Press and described how the Bush administration would respond: "We'll have to work sort of the dark side, if you will. We've got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies." He wasn't kidding. In the panic and paranoia that engulfed the Bush administration after the September 11 attacks, Cheney decided that the end of national security justified any and all means.

Jane Mayer reconstructs in meticulous detail how Cheney and his closest aides legalized torture as American public policy. There were noble administration people who demurred and dissented, but virtually all of them were marginalized. A small "War Council" acted in secrecy to actively exclude all naysayers and normal processes of checks and balances — David Addington, John Yoo, Tim Flanigan, Alberto Gonzales ("an empty suit"), and Jim Haynes. These highly partisan ideologues, a weak president, and interagency rivalry and dysfunction created the "perfect storm." According to Human Rights Watch, "more than 600 U.S. military and civilian personnel were involved in abusing more than 460 detainees." What the public has seen and heard about Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib are only the tip of the iceberg.

The Bush administration boasts that its torture program has been worth the intelligence it gathered, but that's far from clear. Furthermore, "seven years after the attacks of September 11, not a single terror suspect held outside of the U.S. criminal court system has been tried." This is a tragedy in itself because, let's be clear, many of these detainees deserved to be punished. But such prosecutions become impossible when evidence was gathered by torture. And so now America holds hundreds of detainees that it can't prosecute, can't very well release, and can't reasonably hold forever without charges.

In spurning "the last nearly universal moral taboo" of torture, America's reputation among its allies has been badly sullied. Canada, for example, placed the United States on its list of rogue nations that torture (332–333). Our enemies have been enraged and emboldened. Our own military personnel can expect similar treatment. Cheney was careful to pass legislation that granted himself and his colleagues retroactive legal immunity, which is an explicit acknowledgement of what nations around the world have already concluded — that our highest government officials are liable for "prosecutable war crimes" (244). Such prosecution will not happen at home, but as Phillipe Sands has argued in his own book, Torture Team (2008), those responsible for legalizing torture ought to be very careful about traveling overseas. As I write, Mayer's book has been named as a finalist for a National Book Award.