Book Notes

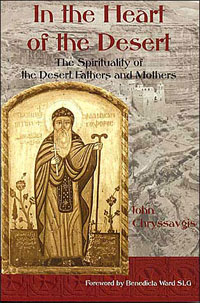

John Chryssavgis, In the Heart of the Desert; The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2003), 163pp.

John Chryssavgis, In the Heart of the Desert; The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2003), 163pp.

I like the two aphorisms that Chryssavgis uses to introduce the overall message of the fourth century desert monastics. From W.H. Auden's In Memory of W.B. Yeats, "In the deserts of the heart, let the healing fountain start." Then, from Isaiah 35:8 (LXX), "The road of cleansing goes through that desert. It shall be named the way of holiness." The desert was the laboratory of Christian discipleship for these saints, and we have much to learn from their experiment. Chryssavgis, Professor of Theology and former Dean at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, has not only studied the desert fathers as a scholar, he has spent time with them as a fellow Christian pilgrim. The result is a wonderful introduction to these early ascetics, similar to Where God Happens (2005) by Rowan Williams. His 18 chapters are brief and to the point. They cover all the pertinent themes you would expect—patience, silence, tears, guidance, detachment, and so on, and then three that are pleasant surprises—the body, the environment, and gender. He quotes copiously from the desert "sayings." The book is complimented by color plates of icons, a simple map of the area, a timeline of people, bibliography, and then the Reflections of Abba Zosimas (6th century) that are translated here for the first time.

The monastics commend themselves for a number of reasons. John the Baptist announced the coming kingdom in the desert. Jesus fled to Egypt as a baby (Matthew 2:12–23), and in Luke's Gospel our first glimpse of him as an adult was when the Holy Spirit drove him into the desert to be tempted by Satan (Luke 4:1). Second, these desert dwellers were practitioners of healing, not abstract theoreticians. They sought personal transformation, not theological information. They believed the wisdom of Diadochos of Photiki (5th century) that "nothing is so destitute as a mind philosophizing about God when it is without him." Third, the desert monastics might strike us as anachronistic oddballs today, and certainly no one would accuse them of being well-adjusted to society, then or now. But we misunderstand them if we construe their bizarre lifestyles as a spirituality of superficial techniques. What they modeled, and what we should emulate, is a transformation of the interior geography of the heart whatever one's exterior circumstances. For them the desert was a specific place, but for us today it can also be a spiritual way. Fourth, I honor the desert mothers and fathers because I want to place myself in the mix of saints who have gone before me. Tradition, said Chesterton, "means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death.” Finally, I love the desert monastics most of all for their profound humanity. These saints modeled what Chryssavgis calls a "spirituality of imperfection" in which one is not ashamed or embarrassed to embrace and affirm one's brokenness, wounds, darkness, and inner demons. They comfortably acknowledged intense struggle as a necessary virtue, praying with Sarapion of Thmuis (4th century), "Lord! We entreat you, make us truly alive."