Book Notes

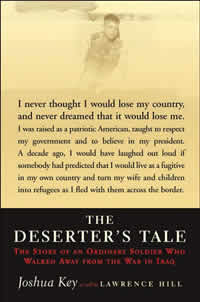

Joshua Key as told to Lawrence Hill, The Deserter's Tale; The Story of an Ordinary Soldier Who Walked Away from the War in Iraq (New

York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007), 237pp.

Joshua Key as told to Lawrence Hill, The Deserter's Tale; The Story of an Ordinary Soldier Who Walked Away from the War in Iraq (New

York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007), 237pp.

Contrary to this book's sub-title, Joshua Key (b. 1978) is no ordinary soldier. In fact, he did the one thing a soldier must never do: "think for myself and question my commanders." Most bravely of all, he listened to the voice of his conscience. His memoir illustrates William Sloane Coffin's warning that in war, "for every boy turned into a man. . . there are five human beings turned into animals."

Key was an army recruiter's dream. He grew up in a two-bedroom trailer in rural Oklahoma with three step dads who beat his mom. His biggest dream was to become a welder. Key describes himself as unabashedly patriotic, so at age 24 he walked into a recruiter's office to escape his grinding poverty. He loved the seventeen weeks of boot camp. He loved the weapons, which in his case were part of his everyday life as a kid in Oklahoma. He especially appreciated the recruiter's assurances that he would be sent to a unit that built bridges, and not into combat.

On April 10, 2003, about three weeks after the United States invaded Iraq, Key deployed to Iraq. He was eager to fight terrorism and defend America. Seven months later he had horrible nightmares, blackouts from drinking, panic attacks and flashbacks. He took sleeping pills, and ripped light fixtures out of the ceiling. Worst of all, he almost lost his soul.

In his seven months of active duty Key conservatively estimates that he participated in 200 house raids. Each successive raid "chipped away at my soul," says Key. Not once did these raids find anyone or anything associated with terrorists. What he and his platoon did do was pillage, plunder, loot, and, in at least one instance, rape normal Iraqi civilians, all with impunity. "We knew that we would not have to give an account for our actions." Key began to realize that his own comrades were terrorizing fellow human beings, not liberating a country, and that "my own moral judgment was disintegrating under the pressure of being a soldier."

Two particular incidents haunt Key even today. On one patrol his platoon came upon four Iraqis who had been decapitated by American machine guns. "We fucking lost it, we just fucking lost it!" a comrade shouted. Two other soldiers just laughed and kicked the heads of the decapitated Iraqis like soccer balls. Then, he witnessed the murder a ten-year-old Iraqi girl who had befriended Key by begging for food almost every day. "I reached for an MRE [to give to her], looked up to see her about ten feet away, and saw her head blow up like a mushroom." He knew enough about guns to recognize the distinctive sound of an American M-16, enough about his surroundings to know that his American comrades were the only people in the area who were armed, and enough about being warned for fraternizing with the "enemy."

After seven months and 200 house raids Key earned a two-week vacation home: "My mind was fried. I hadn't slept more than an hour or two at a time for more than half a year of war. I had heard so many machine guns and mortars that I often found myself hard of hearing after firefights. I could barely string three clear thoughts together. I knew only two things for sure: my own army had made me ashamed to be an American and I was finally going home to see my wife and children." After hiding in Colorado Springs for two months, he fled to Philadelphia where he lived in his car and flea bag motels. With help from the War Resisters Support Campaign in Toronto he moved to Canada, where his initial application for refugee status has been denied. His case is on appeal.