Book Notes

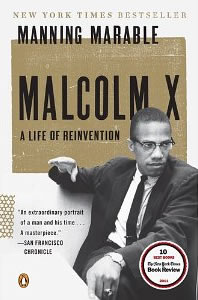

Manning Marable, Malcolm X; A Life of Reinvention (New York: Viking, 2011), 594pp.

Manning Marable, Malcolm X; A Life of Reinvention (New York: Viking, 2011), 594pp.

Manning Marable has written what will stand as the definitive work on Malcolm Little (1925–1965) for decades to come. He emphasizes Malcolm's many reinventions of his carefully crafted persona in order to rescue the historical man from iconic legend as black nationalism's secular saint, and from the "numerous inconsistencies, errors, and fictive characters" in his famous Autobiography that was written with Alex Haley and has sold over six million copies.

The violent death of Malcolm's father and his mother's twenty-four years in an insane asylum "plunged the family into an abyss of poverty." Malcolm was farmed out to neighbors, spent time in a juvenile home, moved to Boston with his half sister, then dropped out of school in the ninth grade. Life as a pimp, drug peddler and petty criminal landed him in jail at the age of twenty. "I don't think anybody got more out of going to prison than I did," he later said. In six years of incarceration Malcolm developed his extraordinary powers of dedication and self-determination through a program of self-education and conversion to the Nation of Islam.

The post-prison Malcolm distinguished himself as a zealous evangelist and national leader in the NOI, a militant sect that had only a tenuous resemblance to orthodox Islam. The NOI was overtly racist and sexist, apolitical and purely religious, preaching absolute separatism from "the white devils." They discouraged members from registering to vote, forbid members from attending the 1963 March on Washington when King gave his "Dream" speech, meted out punitive violence for minor infractions, and demanded unconditional obedience to the dictatorial leader Elijah Muhammad, who claimed to be divine even as he enriched himself and fathered many children by numerous women.

When Malcolm broke with the NOI, he became a celebrity free agent on the world stage but also a marked man. He had been under FBI surveillance since 1950. Trips to the Middle East and Africa opened his eyes to authentic Islam and his cultural roots. World leaders welcomed him. Standing room only crowds thronged him at universities. His evolving understanding of the relationship between race, religion, and politics led to further reinventions. Whereas the earlier Malcolm scorned integrationists like King as Uncle Toms, his later reinventions approximated some version of "multicultural universalism."

At the time of his assassination by the NOI in 1965, observes Marable, Malcolm was "widely reviled and dismissed as an irresponsible demagogue." Many people admired Martin Luther King who worked patiently and accomplished much within the system toward a color blind society. But it was Malcolm X who voiced the rage of many others who thought the system was broken beyond repair, and who encouraged African Americans to celebrate rather than erase color consciousness. History has come full circle. In 1999 the US Post Office issued a stamp commemorating Malcolm X as one of our country's most important civil rights leaders.