Book Notes

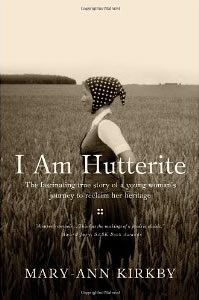

Mary-Ann Kirkby, I Am Hutterite (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 247pp.

Mary-Ann Kirkby, I Am Hutterite (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 247pp.

In 1528 the Austrian hatmaker Jacob Hutter founded a radical Christian community based upon the complete sharing of possessions (see Acts 2:44–45), adult baptism, and non-violence. For that he was burned at the stake in the Innsbruck town square eight years later. His fledgling followers, although likewise persecuted, survived. In 1770 many of them migrated to the Ukraine, from there to New York a hundred years later, then on to South Dakota, where the first Hutterite community in North America was founded in 1874. At the turn of the century entire communities of Hutterites moved to Canada when they were persecuted as conscientious objectors during the war.

Mary-Ann Kirkby's grandfather was among those first Hutterites, and in this bittersweet memoir she pays tribute to her life growing up in Fairholme, Manitoba, one of the 400 Hutterite communities in western Canada and the United States. "This book," she writes, "is my journey to reclaim my past, a past I kept hidden for many years, unwilling to subject myself to ingrained taunts and prejudices."

Like all Hutterite communities, in Fairholme makeup, jewelry, television, radio, newspapers, and photography were strictly forbidden (although not alcohol). Large families, blunt mannerisms, the Hutterisch dialect, plain clothes, famous cookery, sharp humor, and an unrivaled work ethic that produced a thriving community economy were all prized. So too were community segregation by age and gender in both school and church, and conformity to what could be arbitrary and authoritarian leadership.

Therein lay the crisis of conscience for Kirkby's father, who like every Hutterite man had made a vow on his wedding day: "Should I suffer shipwreck of faith, I will not ask my wife or my children to follow me off the colony." But after too many sharp disagreements with his wife's brother (the leader of Fairholme), that's just what he did. He left Fairholme at the age of forty-six with his wife and seven children for the "outside world." He was penniless, had never paid a bill, had a bank account, or held a mortgage. Mary-Ann was ten-years-old.

Gone was her idyllic childhood, and in its place loomed a world that was equal parts fascinating and frightening. It's a shame that this book ends just when the complex questions of an adult individual's sense of self begin to emerge. After learning so much about Kirkby's childhood growing up, we learn essentially nothing about her adult years and transition to life outside the Hutterites. Still, she's crystal clear about her poignant past: "Today I am filled with a deep appreciation of where I have come from and a better sense of where I'm going." I'd love to read a second volume by Kirkby that explores in greater depth just what she means by that.