Book Notes

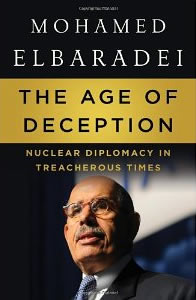

Mohamed ElBaradei, The Age of Deception; Nuclear Diplomacy in Treacherous Times (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2011), 340pp.

Mohamed ElBaradei, The Age of Deception; Nuclear Diplomacy in Treacherous Times (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2011), 340pp.

Blessed are the peacemakers. From 1997 to 2009 Mohamed ElBaradei served as the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency (founded in 1957), and in that capacity as the overseer of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that was founded in 1970 and signed by 198 countries (India, Pakistan and Israel have never been signatories). Despite working at the vortex of such highly politicized issues, ElBaradei and the IAEA were awarded the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize for their work.

ElBaradei takes readers behind the scenes to his meetings with world leaders through effective story telling. Separate chapters detail his own conclusions about nuclear security in Iraq, North Korea, Iran, and Libya. That America would invade Iraq despite the accurate conclusions of the IAEA was a "gross distortion" of everything the IAEA stood for. Cheney had told him personally that although the US was "ready to work with the United Nations inspectors, we are also ready to discredit the inspections in order to disarm Iraq" (53). As for Libya, the 2003 revelation that they were developing WMDs was shocking news to him.

ElBaradei observes three "profound changes" in the nuclear status quo. First, there's the WMD development in rogue states like North Korea and Libya. Whereas knowledge acquisition is easier than ever, and states are catching up on industrial capacity, national intentions remain both complex and opaque. Second, after 2011, it became obvious that not just rogue states but extremist groups seek WMDs. This is no mere "fairy tale," he says. Finally, there's the active black market for nuclear weapons and equipment, what ElBaradei calls the "nuclear Walmart" that involves 30 nations and mysterious figures like A.Q. Khan (about whom he devotes an entire chapter). In fact, the IAEA has identified more than 1,300 cases of black market trafficking in nuclear and radioactive materials.

There are honest differences among experts about these complex matters. There are typically sharp internal disagreements within government administrations. Technology, policy, legality, the media, and strong personalities all come into play. For security in the Middle East, the biggest "elephant in the room" is Israel's nuclear arsenal, which endures thanks to a double standard that insures an asymmetrical nuclear imbalance in the region. The insistence of the United States on maintaining an overwhelming nuclear arsenal while denying nuclear development by other nations is not only a gross hypocrisy; it also provokes paranoia and humiliation. Confrontation, isolation and sanctions will guarantee rather than prohibit proliferation, for they stir pride and resentment. Mutual dialogue, honest compliance, genuine transparency, and respect are in everyone's best interest. "We must abandon the unworkable notion that it is morally reprehensible for some countries to pursue weapons of mass destruction, yet morally acceptable for others to rely on them for security" (172).