Book Notes

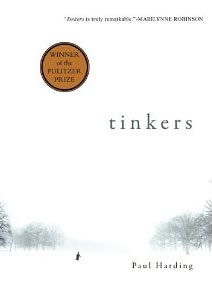

Paul Harding, Tinkers (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2009), 191pp.

Paul Harding, Tinkers (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2009), 191pp.

Paul Harding (b. 1967) took six years to finish college, then spent ten years as a drummer with the rock band Cold Water Flat. At age thirty he decided to write, and enrolled in a summer class at Skidmore College, where by luck his teacher was the Pulitzer Prize winner Marilynne Robinson. Following Robinson's advice, he earned an MFA at the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Like many debut novels by rookie writers, Tinkers lay dormant in Harding's desk for several years, was rejected by numerous publishers, eventually published by a small press that had been in business for only a few years, was ignored by many reviewers, and then sold 7,000 copies its first year. That was before it won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in April 2010.

Tinkers is not a plot-driven novel. Rather, it's a disjointed and dreamy meditation by eighty-year-old George Washington Crosby, who struggles to take stock of his life as he hallucinates in and out of consciousness during the last week of his life. George especially "wants to see his father [Howard] again," who abandoned his family when they tried to commit him to an "insane asylum" because of his epileptic seizures. In another chapter we meet Howard's own father, a Methodist minister plagued by dementia. As George repaired clocks for thirty years, the metaphor of a mechanistic universe plays a central role in the novel. Indeed, George "realized that the silence by which he had been confused was that of all his clocks having been allowed to wind down" — just like his own life was winding down to eternal silence.

Harding's run-on sentences, several more than a page long, distracted me. Some vocabularly felt overwritten — freshet, vastation, scurf, panicles and craquelure. But he excels in describing ordinary objects and haunting family memories with a sense of the sacred, like his favorite pipe rack, an oil painting on the wall, or a carpet on the floor. It breaks the heart, Howard says, "that although we are not at ease in this world, it is all we have, that it is ours but that it is full of strife, so that all we can call our own is strife; but even that is better than nothing at all, isn't it? And as you split frost-laced wood with numb hands, rejoice that your uncertainty is God's will and His grace toward you and that that is beautiful, and part of a greater certainty, as your own father always said in his sermons and to you at home. And as the axe bites into the wood, be comforted in the fact that the ache in your heart and the confusion in your soul means that you are still alive, still human, and still open to the beauty of the world, even though you have done nothing to deserve it. And when you resent the ache in your heart, remember: You will be dead and buried soon enough."