Book Notes

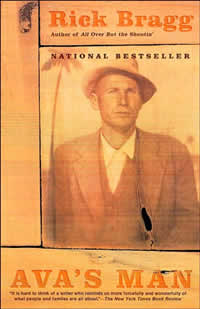

Rick Bragg, Ava's Man (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 259pp.

Rick Bragg, Ava's Man (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 259pp.

With his improbable personal background and deft story-telling, Rick Bragg has earned an avid readership. In All Over But the Shoutin' (1997) he introduced his family of origin, and especially his heroic mother, who epitomized the poorest of poor white trash. His newly released The Prince of Frogtown (2008) makes peace with his violently alcoholic father who repeatedly abandoned his family. Bragg spent one semester in college, then started writing, first high school sports, local stories, anything. In 1993 he won a prestigious Nieman fellowship to spend a year at Harvard, and in 1996 he won a Pulitzer for feature writing at the New York Times. Today he teaches writing at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

In Ava's Man Bragg re-creates the story of his maternal grandfather, Charlie Bundrum (1901–1958), a man of mythic proportions and colorful character who died the year before Bragg was born. Like his other two memoirs, Bragg's narrative works well at several levels. He illustrates the power of place, honors the traditions of a time and place that have been lost to cultural snobbery, exemplifies the ambiguous shadow that one's extended family casts over successive generations, and is just a remarkable wordsmith with the dialect of rural Alabama and Georgia.

Charlie Bundrum was a roofer who could neither read nor write. His people picked the banjo. At the slightest insult to their "honor" they brawled with pocket knives, ax handles, and shot guns. They worked in the mills and picked other people's cotton. "Chollie" fished his beloved Coosa River on a "boat" made from two car hoods that he welded together, he could make a harmonica scream, and he ruined his liver from too many mason jars of moonshine. He eloped with his beloved Ava when she was sixteen and he was seventeen. Ava dipped snuff, her dresses were made from feed and flour sacks, she knew the meaning of welfare cheese handouts, and somehow nourished her eight children through the Depression and two world wars. Charlie moved his family twenty-one times in a decade between the backwoods of Georgia and Alabama, sometimes looking for work, sometimes outrunning the law, and never more than a hundred miles either way.

When Bragg's own alcoholic father deserted his family for the last time, Ava took in Bragg's mother and three sons and became their stalwart caregiver. Bragg owns the horrific domestic violence, superstitions, cockfights, and alcoholism that characterized so much of those times, places, and people. But he dignifies their hard work, the dirt under their fingernails, music, foods, traditions, poetic dialect, and resilience. When Charlie Bundrum died at the age of fifty-one, a line of cars snaked a mile or more to his funeral at Tredegar Congregational Holiness Church. How many of us today can hope for a similar legacy that is so honored by your community?