Book Notes

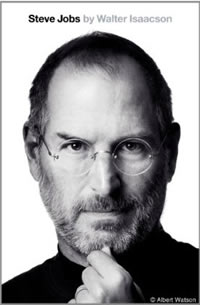

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), 630pp.

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), 630pp.

When Steve Jobs died of complications from pancreatic cancer on October 5, 2011, he had a net worth of $8 billion and Apple was the most valuable corporation in the world. He was, as Walter Isaacson writes in his introduction, "the ultimate icon of inventiveness, imagination, and sustained innovation." Jobs revolutionized numerous industries: product design, the integration of technology and aesthetics, product launch, advertising, personal computers, animated movies (Pixar), music, phones, tablet computers, digital publishing, cameras, and even retail stores. Isaacson tells this story of Jobs's professional success.

He's also unsparing about Jobs's personal flaws, what acquaintances called his "reality distortion field." Jobs lied a lot and he cried a lot. He was a master manipulator, equally adept at flattery and humiliation. His hucksterism rivaled that of P.T. Barnum. He took pride in being cruel, tyrannical and ruthless. He viewed the world in binary extremes; a person, their work, or even a milk shake was either "brilliant" or "horrible." He would scorn a colleague's ideas in private, then later in public take credit for them. A girl friend thought that the Narcissistic Personality Disorder explained Jobs perfectly. Apple CEO John Scully thought he was bipolar. He probably had an eating disorder, given his lifelong compulsion for extreme diets, like eating only carrots for two weeks (which compulsion was one reason he delayed surgery for nine months after his cancer diagnosis, against all the pleadings of doctors and family). He studied Zen all his life and pontificated about enlightenment, but virtually everyone he ever met described him as obnoxious. One of his closest colleagues, neighbors, and family friends, Andy Hertzfeld, once confided, "The one question I'd truly love Steve to answer is, 'Why are you sometimes so mean?'"

Jobs explained to Isaacson: "This is who I am, and you can't expect me to be someone I'm not." He never thought that the rules applied to him, which is why he would park in a handicapped space. Still, every person is more than their worst flaws, and it's fascinating to wonder why an absolute control freak who micro-managed the tiniest of details would cede all editorial control to Isaacson, even the right to see the biography before it was published. Isaacson conducted over forty interviews with Jobs across two years, and more than a hundred more with friends, relatives, competitors, adversaries and colleagues.

My own pop-psychological interpretation is that the biography is a genuine attempt by Jobs to tell the truth about himself — to the pubic, of course, but especially to his own self. It's a final catharsis or confession, late in time but authentic in expression. Jobs knew his personal demons, even if he was unapologetic about them. But only he alone could make sure that this unflattering portrait became public. Ann Bowers, a mother-figure from his teenage years, once described Jobs as "so bright and so needy." Late in his life Jobs confided to her, "I did learn some things along the way. I did learn some things. I really did."