Book Notes

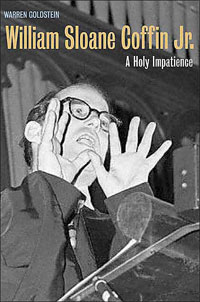

Warren Goldstein, William Sloane Coffin Jr., A Holy Impatience (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 379pp.

Warren Goldstein, William Sloane Coffin Jr., A Holy Impatience (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 379pp.

Today William Sloane Coffin Jr. (born 1924) lives in Vermont, venturing out for an occasional lecture, but in his productive years he was, next to Martin Luther King Jr. and perhaps Billy Graham, the most influential religious voice in America. Goldstein's biography, with which Coffin fully cooperated, details Coffin's colorful and passionate life from his birth into one of the wealthiest and best connected families in New York City (his father's death in 1933 was front page news in the New York Times) to his current retirement.

For over thirty years, first as the chaplain at his alma mater Yale (1958–1975) and then as pastor at Riverside Church in New York City (1977–1987), Coffin was the most prominent voice for liberal Christianity in America. He actively opposed the Vietnam war, and supported the civil rights movement, nuclear disarmament, and gay rights. Coffin was famous for his impatience with academia which in his mind denied or ignored the importance of religious questions. He was the master of aphorisms. He often lamented the "bland leading the bland." He rightly observed that "what is emotionally rooted is not intellectually soluble." Guilt, he suggested after a second failed marriage, "is the last stronghold of pride." As for war, "for every boy turned into a man...there are five human beings turned into animals." His prayers were combinations of spiritual fervor and highbrow eloquence. At a Yale commencement, for example, he prayed for safety "from all perils—the clamorous desires of self-preservation, the trivial, the superficial, and all the pervasive and powerful perversions of our time that would cheapen the humanity of human beings."

Like many great figures, Coffin was a person of contradictions. Goldstein describes him as a "marital disaster" who was "clueless" about domestic life. A brilliant public persona and one of the first Christian media celebrities, he was adrift when the kleig lights dimmed and the music ended. He was unable or unwilling to plumb the depths of his inner emotions and personal relationships: "he was capable of extraordinary commitment to a cause and extraordinary inattention to individuals" (p. 83). This from a man who lamented how conservative Christians knew their Bibles better than they knew the human condition. Coffin was the quintessential insider of the Establishment elite, born into a world of Swiss governesses and chauffeurs. He grew up bilingual (French), later mastered Russian during his four years in the military (1943–1947), and was a master pianist. But it was this same Establishment that he so courageously and boldly challenged. A man's man, a womanizer, and all round bon vivant, he was, nevertheless, dominated by his powerful mother after his father died when he was nine.

After reading a biography of a life lived with such force and focus, however imperfectly, one is left to ponder just where the prophetic Christian voices are today who can relate the Biblical narrative, which Coffin so dearly loved and preached, to the current events of our time. It was Coffin's genius to articulate and live a Christian life in such a way as to show how and why it is relevant, understandable and even attractive (p. 330); indeed, "he never doubted the church's relevance to everyday life" (p. 326). We can only echo one of Coffin's prayers from Reformation Sunday, October 26, 1958, during his first year at Yale. He prayed that we believers might experience unity instead of "sectarian prejudice," for "minds filled with a vision for cooperative discipleship and...hearts alive with the fire of those first disciples." He then implored God "to kindle in our hearts a holy impatience with the sinful factions that have rent Thy Church" (p. x).