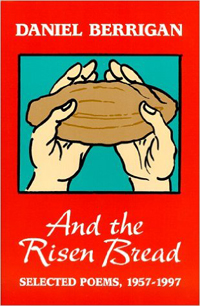

Daniel Berrigan, edited by John Dear and with an introduction by Ross Labrie, And the Risen Bread; Selected Poems, 1957–1997 (New York: Fordham University Press, 1998), 417pp.

Daniel Berrigan, edited by John Dear and with an introduction by Ross Labrie, And the Risen Bread; Selected Poems, 1957–1997 (New York: Fordham University Press, 1998), 417pp.

After Daniel Berrigan died last April, just ten days shy of his ninety-fifth birthday, I read this book of his collected poetry. Berrigan was many things — a Jesuit priest, playwright, author of over fifty books, university professor, and famous peace activist. He spent a long life celebrating the good news of Jesus rather than the bad news of caesar. Most of all, like Elijah of old, he was a troubler of the modern conscience.

In 1968, Berrigan and eight other activists stole 378 draft files of young men who were about to be sent to Vietnam, dumped them into two garbage cans, poured homemade napalm on them, and burned them in the parking lot of the Catonsville, Maryland, draft board. In 1980, he trespassed into General Electric's nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, poured blood on some warhead nose cones, then hammered away to punctuate his prophetic point. For these and similar activities, he spent time on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list, went into hiding, was on the cover of Time Magazine, and eventually spent eighteen months in prison as a convicted felon.

In addition to his well known prophetic social action, Berrigan was also deeply devoted to sacred and artistic contemplation. He published eighteen volumes of poetry. His very first volume of verse, Time Without Number (1957), was nominated for a National Book Award and won the prestigious Lamont Prize for poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

This volume collects four hundred pages of poetry that Berrigan wrote across forty years. It's a wonderful collection, but it could have been so much better. There's a brief biographical introduction that could have been greatly expanded. It's not made clear which poems came from which previously published books. There's no author or subject index, bibliography, or footnotes at the end of the book. There are absolutely no historical explanations or introductions to any of the poems, which leaves the average reader clueless about what are otherwise important people and places in Berrigan's poems. This becomes even more important because most of his poetry is not easy to read; it's free verse, with non-traditional wording, syntax, grammar, meter, rhyme, and form. I would also add that it's not clear to me how much or little poetry Berrigan published after 1997 — he lived for another twenty years. All of which is to say that, now that Berrigan has died, I hope someone will collect, edit, and annotate a complete and critical edition of his poetry.

These poems capture Berrigan's faith that burned like fire, but they also reveal his feelings of futility (thus the recurring theme of the holy fool), and of his frustrations with the institutional church. The poems riff on Biblical themes, his experiences of the poor on the streets of New York City, personal friends and family members, a whole section of prison poems, creation and the world of nature, and his analysis of the American ethos.

In his meditation on 1-2 Kings, The Kings and Their Gods (2008), Berrigan leaves us with this challenge. "One must urge (to his own soul first) a firm rebutting midrash; bring Christ to bear. Read the gospel closely, obediently. Welcome no enticements, no other claim on conscience. Mourn the preachers and priests whose silence and collusion signal plain revolt against the gospel. Enter the maelstrom, the wilderness; flee the claim that would possess your soul. Earn the blessing; pay up. Blessed — and lonely and powerless and intent on the Master — and, if must be, despised, scorned, locked up — blessed are the makers of peace."