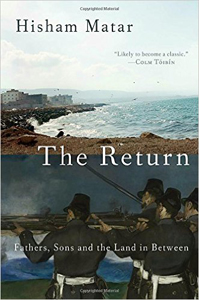

Hisham Matar, The Return; Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between (New York: Random, 2016), 243pp.

Hisham Matar, The Return; Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between (New York: Random, 2016), 243pp.

This memoir by the Libyan writer Hisham Matar (b. 1970) begins about seven months after the fall of Tripoli and the Gaddafi dictatorship in August of 2011. In March of 2012, Matar and his wife Diana returned to Libya for the first time in thirty-three years, since his family had left when he was eight years old. At the age of fifteen, Matar packed off to boarding school in England, where he lived for the next twenty-nine years. No one at that time expected the grim and chaotic future that awaited Libya not long after — it was a period of patriotic optimism during the Arab Spring.

Matar's return was filled with fear and longing, and for good reason. In 1990, when he was nineteen and still in England, his father Jaballa, a prominent figure in the Libyan opposition movement (to the tune of $15 million a year), was kidnapped by Gaddafi's thugs. He was then sent to the notorious Abu Salim prison in Tripoli, a hell hole known as "The Last Stop" because of its torture, cruelty, and, in 1996, the execution of 1,270 prisoners. Except for three letters that were smuggled out, Matar never heard from his father again.

Hisham had returned home, but would Jaballa ever return? His trip in 2012, after twenty years of anguish, and a campaign that reached to the highest levels of British diplomacy and even Gaddafi's son Seif, was meant to answer that question. It's a story fraught with hope and dread. "When your father has been made to disappear for nineteen years, your desire to find him is equaled by your fear of finding him. You are the scene of a shameful private battle."

What happened to his father? Was he shot? Hanged? Executed in the 1996 slaughter? Could he still be alive? He had sent over 300 letters of inquiry without a single response. Rage and bitterness have filled his days for twenty years, but he still cannot resist hope. He's obsessed to learn what happened to Jaballa, who's absence remains very much a presence of its own sort. All he has left are a few photos, those three prison letters, family stories, and unresolved questions about his father's fate that haunt him to this day.

Hisham Matar's work has won numerous awards, and been translated into twenty-nine languages.