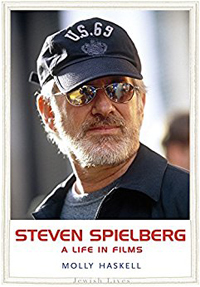

Molly Haskell, Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 224pp.

Molly Haskell, Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 224pp.

This short biography is one of the titles in Yale University Press's "Jewish Lives" series of "interpretive biographies" of Jewish figures in literature, religion, philosophy, politics, culture, economics, art, and the sciences. About thirty titles are already published, with about the same number still forthcoming. For those who don't have the inclination to read the 640-page Steven Spielberg: A Biography (2011, second edition) by Joseph McBride, the film critic Molly Haskell has written an appreciative but not uncritical biography of one of the greatest film makers ever.

Spielberg turned seventy in December of 2016, and so after fifty years of making movies, it's become easier to consider his "staggering output" in a more nuanced light. For decades Spielberg has been an easy target for film snobs. He has epitomized the commercial-corporate mogul who has made fluff movies for mass appeal — a fact he has acknowledged with what Haskell calls "disarming candor." When he was only twenty, he told a student reporter, "I don't want to make films like Antonioni or Fellini. I don't want just the elite. I want everybody to enjoy the films." No one has been more successful at making movies as financial juggernauts — the 1982 movie ET had 200 official product tie-ins, and Spielberg was making a reported $500,000 a day on his share of the profits (99). A ruthless negotiator, despite his carefully crafted regular guy persona, today he has a net worth of $3.7 billion.

Other critics like Pauline Kael complained that Spielberg's movies "weren't about anything." The absence of any deeper meaning, the misogynist caricatures of women, the regression into adolescence, the gratuitous violence — was this not a corrosive dumbing down of cultural taste? Was he not an "artistic lightweight" (147)? There is truth in these criticisms, says Haskell, but they are tempered by his later works like Schindler's List, after which, she says, "all bets were off."

Spielberg never gives interviews to biographers, so Haskell is left to interpret his life by reviewing his movies. This makes for choppy reading — 18 chapters in 200 pages, with a few pages given to film after film. Still, this isn't all bad, because Spielberg himself has said that "everything about me is in my films." And what a life, for a poor student who never finished college, much less went to film school. Love him or hate him, Steven Spielberg is what Geoffrey O'Brien called "something of an anthology of superlatives, a walking lifetime achievement award." (NYRB, February 23, 2017).