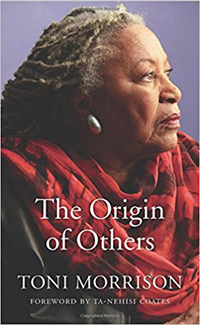

Toni Morrison, The Origin of Others (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 114pp.

Toni Morrison, The Origin of Others (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 114pp.

Toni Morrison's (born 1931) long and illustrious career as an editor, novelist, essayist, playwright, and librettist has earned her numerous awards — a Nobel Prize for literature (1993), a National Book Critics Circle Award, and a Pulitzer Prize (1988). Today she is professor emerita at Princeton in the Humanities, where she "retired" in 2006. This little book originated as the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard in 2016, during Obama's last year in office, and includes a ten-page foreword by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

There are many ways to "other" and exclude people, like wealth, class, and gender, but as you might expect, in this book Morrison focuses on race, what Coates calls in his foreword "the oldest and most potent form of identity politics." Although she includes a few personal stories, for the most part Morrison engages with a broad array of literary texts. Even in a novel like Uncle Tom's Cabin we see how slavery was romanticized and its subjects infantilized. In Flannery O'Connor we observe an accurate portrayal of the benefits that accrue to those who marginalize others, while in Faulkner and Hemingway we see the "fetish" of skin color as "the ultimate narrative shortcut." In contrast, Morrison has tried to write what she calls "non-colorist literature about black people."

"Color-coding" occurs among blacks themselves, observes Morrison. I'm reminded, for example, of the memoir Negroland (2015) by Margo Jefferson, in which she describes how as part of the black aristocracy she was taught that "most other Negroes" should have emulated you, but in fact behaved in ways that "encouraged racial prejudice;" or the novel Americanah (2013) by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in which the protagonist Ifemelu encounters unexpected complexities when she returns to her homeland in Nigeria after thirteen years in the United States. More broadly and sadly, Morrison observes "how vulnerable we [all] are to distancing ourselves and forcing our own images onto strangers as well as becoming the stranger we may abhor." Still, we are not fated or destined to racist Othering; we can do better, and Morrison's book helps us to do just that.