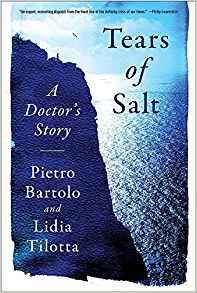

Pietro Bartolo and Lidia Tilotta, translated from the Italian by Chenxin Jiang, Tears of Salt: A Doctor's Story (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), 206pp.

Pietro Bartolo and Lidia Tilotta, translated from the Italian by Chenxin Jiang, Tears of Salt: A Doctor's Story (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), 206pp.

This memoir of moral courage and indignation is set among the refugee crisis on Lampedusa, a tiny and isolated Italian island just eight miles square and that sits only seventy miles from the north coast of Africa. In the last twenty years, 400,000 migrants have landed on Lampedusa, fleeing war, poverty, and ethnic strife. About 15,000 people have died trying.

The physician Pietro Bartolo was born on Lampedusa in 1956 to a family of seven children. Like most men there, his father was a fisherman, and like most people on Lampedusa, they were poor. He never wore shoes as a little boy, and was packed off to school at the age of thirteen because the island had no high school. But after studying medicine, he returned, and spent five years as the deputy mayor and the councilor of health.

For twenty five years now, since 1992, he has headed the only medical clinic on the island. As such, he's the first medical person that the migrants meet, and the point person of perhaps the signal global crisis of our time. Sometimes he is their savior, and often he is their coroner. "On Lampedusa," he says, "I have seen it all." And no, despite all his experiences of horror, despondency, helplessness, and futility, "you never get used to it."

Bartolo speaks up for those who have no voice. Like fifteen-year-old Jerusalem from Eritrea. Omar from Tunisia. A Sudanese girl named Sama who arrived with a pet cat. The brothers Hassan and Mohammed from Somalia. A teenager from Ghana, Joi from Nigeria, Amina from Libya, and Jasmine who arrived on a boat with 800 migrants. "My USB drive fills up every day with their names. I catalogue their names and preserve their stories with the meticulousness of an archivist."

Bartolo devotes a chapter to how he was featured in Gianfranco Rosi's strange movie Fire at Sea (2016), which won the top prize at the 2016 Berlin Film Festival, and was a finalist for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. In the film he's the voice of conscience and compassion. The lucky refugees who make it ashore with their foil blankets, dehydrated and malnourished, many with burns from diesel-soaked clothes, face a new set of problems. They are searched, registered, photographed, processed, and, it would appear, forgotten — out of sight and mind to the islanders and the world. They wait and hope. Whereas questions about policy are admittedly complex, when it comes to the people he treats, Bartolo has a message for us all: "It is the duty of every human being to help these people."