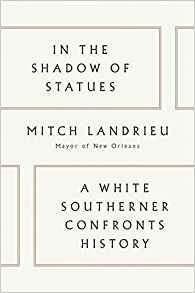

Mitch Landrieu, In the Shadow of Statues; A White Southerner Confronts History (New York: Viking, 2018), 227pp.

Mitch Landrieu, In the Shadow of Statues; A White Southerner Confronts History (New York: Viking, 2018), 227pp.

Mitch Landrieu (born 1960) got a first and very bitter taste of racist politics when he was only thirteen years old. That's when he received death threats as a little boy because of the progressive policies of his father "Moon" Landrieu, the two-term mayor of New Orleans (1970–1978). Mitch was born the fifth of nine children in a deeply Catholic family, he grew up in the mixed-race neighborhood of Broadmoor, and then after law school went on to serve as the lieutenant governor of Louisiana (2004–2010), and eventually, like his father, as the two-term mayor of New Orleans (2010–2018). His sister Mary is a U.S. Senator.

Some pundits see this volume as the obligatory autobiography that's released before a presidential run, and it's true that Landrieu has attracted national attention among some leading analysts. But taken at face value, it's also an interesting read about a life dedicated to progressive politics in the context of a city plagued with a long history of racism. New Orleans, it turns out, was home to the largest slave market in America. There are also separate chapters in this book on Louisiana's David Duke and Hurricane Katrina. Despite what he calls an idyllic childhood in a loving family, where there was never a time when issues of race were not both personal and political, Landrieu says that it still took him forty years of "transformative awareness" to finally "get it."

His epiphany about racism culminated in his bitterly controversial decision to remove four confederate monuments in the heart of New Orleans — Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, and then a monument that honored the White League (an organization of racial militants). For the first time in his life, Landrieu says, he came to see these monuments not just as harmless reminders of history, but as "totemic" pieces about white supremacy, and "political symbols" about a war whose purpose was to preserve slavery. The monuments "sanitized history" in the worst possible way. When he announced the decision to remove them in 2015, he couldn't even find a contractor that was willing to do what turned out to be deeply dangerous work. Death threats and legal challenges stalled the controversy, but on April 24, 2017, the removal began, and was completed about a month later. And so for its 2018 tricentennial, New Orleans stands just a little taller and prouder thanks to a politician who followed his conscience.