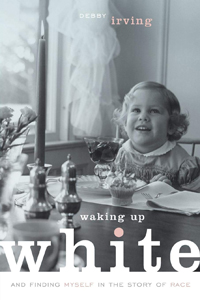

Debby Irving, Waking Up White And Finding Myself in the Story of Race (Cambridge: Elephant Room Press, 2014), 273pp.

Debby Irving, Waking Up White And Finding Myself in the Story of Race (Cambridge: Elephant Room Press, 2014), 273pp.

Debby Irving begins and ends her book about racism with a vivid memory from her childhood. When she was five years old, she asked her mother, "whatever happened to all the Indians?" Her mother answered that the Indians ruined themselves by their heavy drinking. Even at that tender age, writes Irving, "that made no sense to me." That was the moment when "my soul first cracked, letting in a sip of cognitive dissonance that would be added to over the years." (4, 245). In 46 short chapters, each of which ends with a discussion question, Irving describes her long and painful journey from white privilege to "racial justice advocate" (219).

Irving's story is one of intersectionality — discrimination or bias due to the intersection of racism with other forms of bigotry, like sexism (gender racism) or homophobia (queer racism). In her case, her racism intersected with economic classism. She was born in 1960 in an exclusively white part of Boston, into a thoroughly "New England WASP family." This meant restrained emotions, frugality, extreme modesty, the country club, the boat club, annual summer vacations to the family cabin, a father who went to Harvard Law School, numerous family connections to all sorts of similarly powerful people, etc. Bit by bit, and much to her credit, Irving came to realize how much she had been formed by her sheltered family life, and how she projected that onto people who came from different backgrounds.

I especially enjoyed two aspects about Irving's book. First, there are dozens of deeply personal stories that she shares, most of them quite unflattering, as she woke up to her deeply embedded class racism. Second, many of the questions at the end of the book and in those stories are quite helpful. For example, if you are white, do you ever think about having white skin? Do you think of white people as being a race? Why is it that whiteness is considered a superior norm against which other skin colors are judged? Consider the many privileges that being white affords, like never having to speak for all the people of your racial group, shopping without wondering if you are being followed, raising your kids to see police as safe and wise protectors who can help you, or not worrying about other people secretly wondering how you attained a prestigious job or education, etc.

I would add just one note to this book and others like it: inspiring stories are no substitute for radical changes in policy and legislation, as pointed out, for example, by Ibram Kendi in his book How to Be an Antiracist, the article by Saida Grundy, "The False Promise of Anti-racism Books" (The Atlantic, July 21, 2020), and John McWhorter, "The Dehumanizing Condescension of White Fragility" (The Atlantic, July 15, 2020). Consciousness raising is a good thing, Grundy admits, but it's only a beginning and not a substitute for the heavy lifting of systemic changes. Raising awareness is good, but by itself does not correct injustices. Racquel Gates makes similar points in her article "The Problem with 'Anti-Racist' Movie Lists" (July 17, 2020, New York Times).

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net