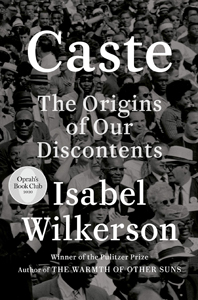

Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (New York: Random House. 2020), 476pp.

Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (New York: Random House. 2020), 476pp.

It's been ten years since Isabel Wilkerson published her award-winning book The Warmth of Other Suns (2010) about America's "Great Migration." Between 1915 and 1970 six million blacks migrated from the south to the American north and west. When the migration began, about 90% of blacks lived in the south; sixty years later only 50% of them did. The black population in Chicago swelled from 44,000 to over a million. Detroit's skyrocketed from 1.4 percent to 44 percent.

Wilkerson humanized this history by telling the stories of three individual migrants who represent the three main paths that blacks took out of the south — up the Atlantic seaboard to the northeast, up the spine of the country to the cities of the midwest, and then west mainly to California. These people were fleeing what Wilkerson called in Warmth a "feudal caste system." At the beginning of her new book Caste, she recalls her epiphany upon realizing that in Warmth she was actually "not writing about geography and relocation, but about the American caste system." The jarring notion of caste now receives her book-length treatment, which the NY Times called "an instant classic" even before it was released.

Throughout human history, says Wilkerson, there have been "three caste systems that have stood out" —Nazi Germany, India, and the United States, where "race is the primary tool and the visible decoy, the front man, for caste." Our American caste system began with the first slaves from Africa who were brought here in 1619, which means that slavery and its dreadful consequences have been with us for 246 years, whereas it's been only 155 years since its putative end with the Civil War in 1865. So, the caste system hasn't been an exception, an aberration, or a passing "chapter" of American history, it has been the socio-economic foundation upon which the country has been built.

Wilkerson admits that readers might be surprised with her comparisons to Nazi Germany and India, and that the notion of caste is not a term we usually apply to America. She's careful to draw both comparisons and contrasts, and also notes the interplay of race, class, and caste. Nonetheless, she identifies "eight pillars of caste" that are "disturbingly present" in all three countries. In contemporary parlance, our 246 years of slavery were nothing less than a carefully crafted and comprehensive system of state sponsored terror and torture "that the Geneva Conventions would have banned as war crimes." The Nazis, in fact, carefully studied American racism when it crafted its own caste system. And if you follow Wilkerson's footnotes, you learn that there is a substantial literature that compares the Indian and American caste systems.

In her epilogue, Wilkerson deflects criticisms that she has not offered any solutions. "The goal of this work has not been to resolve all of the problems of a millennia-old phenomenon, but to caste a light onto its history, its consequences, and its presence in our everyday lives and to express hopes for its resolution." Such hopes begin with a "radical empathy" that is based upon education and awareness (380, 386), and that insists upon the common humanity of all people.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net