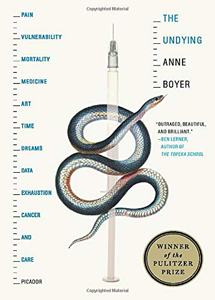

Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2020), 308pp.

Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2020), 308pp.

Back in 2014, one week after her forty-first birthday, the American poet and essayist Anne Boyer was diagnosed with a rare and highly aggressive "triple negative" form of breast cancer. She was a single mother of an eighth grader, living in a two-bedroom apartment, she had no savings, no nearby family, and a job where she was advised never to let on that she was sick. Her unapologetically angry memoir about her cancer experience won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for general non-fiction.

Cancer in itself is bad enough, and Boyer describes in painstaking detail what that is like: the poison of chemotherapy, followed by a double mastectomy (out patient!), then returning to work ten days later because she was out of sick leave. But what really makes cancer so insidious, in her view, are the many ways that one's sickness is necessarily mediated through all sorts of "systems." Like the health care system, or the "capitalist medical universe." Elsewhere she calls this a "ruinous carcinogenosphere" (78, 119), and an "ideological regime."

So, beyond describing her personal experience, Boyer offers a furious social-cultural critique, and almost nothing escapes her wrath: the insurance industry, drug companies, medicine as profit, gender, politics, race, economics, cancer fakers, spurious home remedies, and especially the pink ribbon charity Susan G. Komen for the Cure that, to date, has raised nearly a billion dollars (183). This social-cultural deconstruction is supported by philosophic reflections on the likes of the first century Aristides, Arendt, Sontag, Foucault, Donne, and Goethe. It comes as no surprise, then, that one of Boyer's heroes is a woman who said no to this brutal "regime" and refused treatment.

Perhaps rage is a much needed push back against our culture's many myths about cancer. But it's not the only authentic way to parse cancer. I especially appreciated three other cancer memoirs. There's Julie Yip-Williams, The Unwinding of the Miracle (2019). As a ruthless realist, Yip-Williams describes how in the course of her cancer she changed from a "belligerent warrior" who would win her "war" with the disease to a "contemplative philosopher" who distrusted the "rah-rah-rah nonsense" and the "cottage industry of denial" that exists among some sectors of the cancer community. I also appreciated Kate Bowler's Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I've Loved (2018). Bowler, a historian at Duke Divinity School, was diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer when she was thirty-five. Finally, there is the remarkable memoir by Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air (2016). Kalanithi had finished some twelve years of training — medical school (Yale), a degree in the history and philosophy of science and medicine (Cambridge), and then neurosurgery training and a post-doc in neuroscience (Stanford), when, at the age of thirty-six, he was diagnosed with stage IV metastatic lung cancer — a terminal diagnosis that was extremely rare for someone his age. His memoir, which he worked on right up to his death in March of 2015, describes how he and his wife Lucy, an internist at Stanford, struggled to find meaning in his dramatic role reversal — from being a neurosurgeon who had won prestigious national awards to becoming a patient in a hospital gown sitting in the very same examine rooms where he had treated hundreds of his own patients.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net