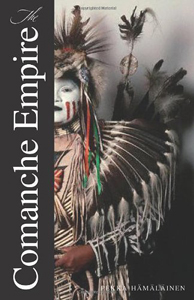

Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven: Yale, 2008), 512pp.

Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven: Yale, 2008), 512pp.

I read this book after a Stanford University professor told me that it radically altered how he viewed the history of America's Indians. "You'll never think about Indian history in the same way," he said. Just about everyone who has read Comanche Empire agrees with that verdict. Pekka Hämäläinen's book is a classic example of revisionist history. It has won over a dozen awards (and been translated into French and Spanish) for how it recovers a lost story, and questions fundamental assumptions about America's indigenous tribes and their relationship to the colonial empires.

In what one scholar called the "cameo theory of history," American indigenous peoples are a sort of blip on the graph of history: they "make dramatic entrances, stay briefly on the stage, and then fade out as the main saga of European expansion resumes." In his book 1491, Charles Mann similarly describes this popular, powerful, and misleading stereotype, that Columbus discovered a sort of timeless and unspoiled Eden, and a people who lived, as it were, outside of history. In this view, the Indians "were suspended in time, touching nothing and untouched themselves, like ghostly presences on the landscape." Like Mann, Hämäläinen categorically rejects the various caricatures of American Indians — that they lacked agency, that they were barbaric savages of a primitive and pathological violence, "tragic victims" of European colonialism, or "bit players" on the stage of history. Far from it.

His book "is about an American Empire that, according to conventional histories, did not exist. It tells the familiar tale of expansion, resistance, conquest, and loss, but with a reversal of usual historical roles: it is a story in which Indians expand, dictate, and prosper, and European colonists resist, retreat, and struggle to survive." In meticulous detail, Hämäläinen documents how from about 1700 until 1875, the Comanche Empire rose to dominate the violently contested lands of the American Southwest, the southern Great Plains, and northern Mexico. The Comanches accomplished this dramatic reversal "through a creative blending of violence, diplomacy, extortion, trade, and kinship politics." Indeed, they "imposed their will on neighboring polities, harnessed the economic potential of other societies for their own use, and persuaded their rivals to adopt and accept their customs and norms." They were nothing less than the dominant people of that particular time and place — an Empire in its own right.

Since 2012, the Finnish historian Pekka Hämäläinen has been the Rhodes Professor of American History at the University of Oxford.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net