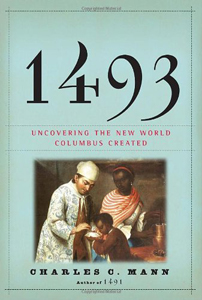

Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World That Columbus Created (New York: Vintage, 2011), 690pp.

Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World That Columbus Created (New York: Vintage, 2011), 690pp.

In his previous best-seller and award-winning book 1491: New Revelations About the Americas Before Columbus, Charles Mann explored a simple question that turns out to be quite complex: what was the world like that Christopher Columbus encountered when he landed on an island in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492? Exactly who were the "first Americans?"

The most popular, the most powerful, and the most misleading stereotype is that he discovered a sort of timeless and unspoiled Eden, and a people who lived, as it were, outside of history. In this view, the Indians "were suspended in time, touching nothing and untouched themselves, like ghostly presences on the landscape." Mann offered a radical challenge to these conventional ideas. The so-called "New World" that Columbus encountered was very old, densely populated, and highly sophisticated.

1493 is the obvious sequel to 1491. Mann's subtitle suggests his thesis. Columbus did not "discover" a new world, rather, he unwittingly created a new world. In 1493, Mann explores what happened to the very old "new" world after and because of Columbus. Both in his Prologue and in his Acknowledgements, he credits the book Ecological Imperialism (1986) by Alfred W. Crosby and Crosby's thesis of a "Columbian Exchange" (the title of another book by Crosby), an idea that he uses as an organizing principle for the entire book. The Columbian Exchange was the creative collision between the ecological and the economic, between east and west, north and south, the result of which was what we now call globalization—500 years ago.

"What happened after Columbus was nothing less than the forming of a single new world from the collision of two old worlds." It ushered in our so-called Homogenocene, the homogenizing or mixing of unlike substances to create a uniform blend. The Columbian Exchange brought corn that originated in Mexico to Africa, and sweet potatoes that originated in the Andes to Asia. It took horses and apples to the Americas, and rhubarb and eucalyptus to Europe. Tobacco, which originated in the Amazon, and sugar cane from New Guinea, both became global manias, and drove the need for slave labor (a major section of the book). There was also an ominous exchange of organisms like insects, grasses, bacteria and viruses that had dreadful consequences like the Great Famine in Ireland and small pox and malaria among Native Americans.

The globalizing consequences of Columbus's voyage brought mixture of blessings and curses, economic gains and ecological curses, and social disruptions of all sorts. "Since Columbus," writes Mann, "the world has been in the grip of convulsive transculturation." The "ecological paroxysm" and the "economic convulsion" that began in 1493 helped to establish our modern world. "Never before had so much of the planet been bound in a single network of exchange."

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net