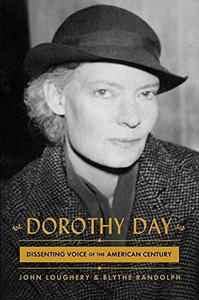

John Loughery and Blythe Randolph, Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020), 436pp.

John Loughery and Blythe Randolph, Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020), 436pp.

When Dorothy Day's memoir The Long Loneliness was published in early 1952, the New Yorker commissioned a two-part profile about the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement (Dwight Macdonald, "The Foolish Things of the World," parts 1 and 2, October 4 and 11, 1952). The very first sentence declared that "many people think that Dorothy Day is a saint and will some day be canonized." That sort of talk always irritated Day (1897–1980). "Don't call me a saint," she would say, "I don't want to be dismissed that easily."

Prior to her adult conversion in 1927, Day called herself a "dedicated atheist." She had a well deserved reputation as a prodigious drinker, a serial lover, a formidable intellectual, and a radical non-conformist. She was twenty when she experienced her first arrest and incarceration. The grief of an abortion led to two suicide attempts. Nonetheless, after her conversion, along with the "holy fool" Peter Maurin, in 1933 she started the Catholic Worker movement — the newspaper (still in print today), the houses of hospitality for the hungry and the homeless, and the rural farm communes. Today the movement claims some 240 autonomous communities.

Day certainly wasn't a saint in the popular sense of the word, except perhaps in her fanatical "cultivation of worldly failure." In their definitive account of her life and work, John Loughery and Blythe Randolph describe her as a "great anomaly." She was an orthodox Catholic and a political radical who was nonetheless profoundly at odds with both secular and religious institutions. She never voted, never registered as a socialist, and despite many accusations, was never part of the Communist Party. She protested the Vietnam war but opposed the excesses of the counter culture of that day. One person described Day as an "autocratic ascetic." Her failures as a mother to her only child Tamar were "painfully evident" and much discussed by those who knew her, not to mention a source of profound grief to Day herself. The chaos of the CW houses of hospitality is legendary.

In her family memoir Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (2017), Kate Hennessy similarly describes her grandmother as a paradoxical woman of many "complexities and contradictions." Stanley Vishnewski, a close friend of Day who joined the CW in 1934 and remained with them until his death in 1979, once observed that "people came to the Catholic Worker expecting to find saints, and instead they found human beings." Robert Ellsberg, who transcribed and edited Day's handwritten diaries, and spent five years with the CW after dropping out of Harvard, says that Hennessy's biography reminds us that "holy people are actual human beings." The real martyrs, it turns out, are those who have to live with the saints.

Despite all this, the Catholic Church has begun the official process toward the canonization of Dorothy Day as a saint. For more on her life, see the PBS documentary "Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story (March 6, 2020), which aired in conjunction with the release of the biography by Loughery and Randolph. See here:

https://www.pbs.org/video/revolution-of-the-heart-the-dorothy-day-story-lwz697/

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net