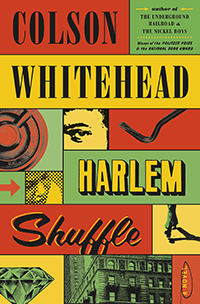

Colson Whitehead, Harlem Shuffle (New York: Doubleday, 2021), 318pp.

Colson Whitehead, Harlem Shuffle (New York: Doubleday, 2021), 318pp.

Colson Whitehead (born 1969) is on nearly everyone's short list of the most important writers in the United States today. He has written ten books of fiction and non-fiction. His many awards include two Pulitzer Prizes for his novels The Underground Railroad (2016), which also won the National Book Award, and The Nickel Boys (2019), a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Guggenheim fellowship.

Harlem Shuffle is a book of crime fiction that's set in Harlem in the 1960's. Upon its release in September of 2021, it debuted at #3 on the NYT bestseller list. In fact, Whitehead was born and raised in Manhattan, and lives in New York City today. He has called the novel a "love letter" to Harlem. I would describe that as a deeply complicated love. The story features a conflicted protagonist, Ray Carny, and his bittersweet love for his city.

The Harlem of Whitehead's novel is populated by thugs, gangsters, pimps, embezzlers, and an assortment of lowlifes. A baseball bat is standard equipment for a bar owner. Racial tensions simmer in the ethnic mix of Jews, Italians, southern blacks, and West Indians: "everyone who came uptown had crossed some violent ocean." It is a world of flop houses, dingy bars, and urban blight for those who cannot escape it. "A tendency toward moral irregularity made you a regular." This is a Harlem where you must go along to get along.

It's not just the bad people who are bad; the good people are also bad — the crooked cops, judges, bankers, accountants, and founding fathers of New York City who are what passes for mainstream culture, including Carny's in-laws. They "could pass for white," are "race-conscious and proud," and spiteful of his dark skin color. "Crooked world, straight world, same rules — everybody had a hand out for the envelope." Harlem "took everything into its clutches and sent it every which way," and so "there were no shortage of reasons to get out of Harlem if you could swing it."

Carny struggles with his city but also with his soul. He's a bad good guy who lives a double life as a striver and a crook. He was "only slightly bent when it came to being crooked, in practice and ambition." In his straight life he owns a furniture store, and loves his wife and kids, while in his crooked life the furniture store is a fence for stolen goods. Carny is like a horse with two riders. He has a "midnight" side and a "daylight" side. His moral ambiguity is marbled and not merely segmented. In his better moments he understands his debasement: "he had descended rungs into the sewer and become another shabby player in the city's sordid theater."

However much Whitehead loves Harlem, Carny fantasizes about leaving. Who would not want to flee "a dark apartment with a back window that peered out onto an airshaft and a front window kitty-corner to the elevated 1 train," and a tangle of lies with bad actors that threaten his very life? Having moved up and out of Harlem one time, Carny imagines yet another move to Strivers' Row: "It was such a pretty block and on certain nights when it was cool and quiet it was as if you didn't live in the city at all." Perfect. Such is Harlem love.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net