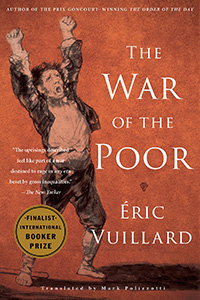

Éric Vuillard, The War of the Poor (New York: Other Press, 2020), 79pp.

Éric Vuillard, The War of the Poor (New York: Other Press, 2020), 79pp.

In his magisterial book The Reformation (2003), the Oxford historian Diarmaid MacCulloch describes how the Protestant Reformation tore through Europe from the Baltics to the Black Sea and the Atlantic Isles to Russia, reconfiguring the geo-political maps, social structures, economies, churches, universities, ideas, and the everyday lives of ordinary people. It was an age when Christians tortured, burned, beheaded, and quartered each other over baptism and the Lord's Supper. Beginning with the Peasants' War in 1525 and lasting until the Peace of Westphalia in1648 that ended the Thirty Years War, there were precious few times and places free of barbarism. It was, says MacCulloch, a time of "extreme mental and physical violence."

Éric Vuillard's little book dramatizes the violence of the Peasants' War from 1524 to 1525, which ended when the aristocracy slaughtered 100,000 poor and poorly organized insurgents, and in particular the prominent role played by the controversial radical Thomas Müntzer (1489–1525) in that debacle. Müntzer was part of the "radical Reformation" that wasn't content merely to translate the Bible into the common vernacular, encourage lay people to read it for themselves, redefine the sacraments, and dismiss the clergy as a hindrance to their relationship with God. They demanded more than a promise of equality in heaven; they wanted it here and now on earth. When Müntzer read the Psalms, the Beatitudes, or Mary's Magnificat, he interpreted them to signal the apocalyptic end of the world, and the beginning of a new political and social order that included the redistribution of wealth and power. He understood himself to be "the sword of Gideon."

In his infamous response called Against the Murdering Hordes of Peasants (1525), Luther sided with the prevailing powers of the secular nobility: "Therefore, whosoever can, should smite, strangle, and stab, secretly or publicly, and should remember that there is nothing more poisonous, pernicious, and devilish than a rebellious man. Just as one must slay a mad dog, so, if you do not fight the rebels, they will fight you, and the whole country with you." For his part, Müntzer derided Luther as "the easy-living flesh of Wittenberg."

The Peasants' War was a catastrophe for farmers, miners, weavers, laborers, and the commoners. Müntzer was captured, tortured, and beheaded. And so ended Europe's largest and most widespread popular revolt prior to the French Revolution of 1789. The fiasco later became grist for the intellectual mill of Marx, Engels (who wrote a book about it), and many other historians and economists. And the takeaway for us today? I like how Chris Hedges puts it in his back cover blurb: "There are serious consequences to unfettered greed and a callous disregard for the plight of the working class by a rapacious oligarchic elite."

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net