Book Notes

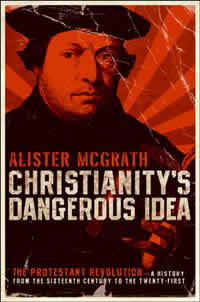

Alister McGrath, Christianity's Dangerous Idea; The Protestant Revolution—A History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2007), 552pp.

Alister McGrath, Christianity's Dangerous Idea; The Protestant Revolution—A History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2007), 552pp.

According to David B. Barrett, author of the World Christian Encyclopedia, contemporary Christianity has experienced an explosion of what he calls “neo-apostolic” movements. Distinct from traditional Protestants, and numbering about 400 million Christians in 20,000 “movements,” neo-apostolic believers “reject historical denominationalism and restrictive or overbearing central authority.” In Barrett's estimate they will constitute 581 million members by the year 2025, 120 million more than all Protestant movements. In two decades these sectarian movements will outnumber Orthodox and Protestant Christians and be almost half the size of worldwide Catholicism.

Welcome to the blowback of what Alister McGrath, professor of historical theology at Oxford University, calls the revolutionary and dangerous idea of the Protestant Reformation—that ordinary Christians, as opposed to any centralized religious authority, could and should read the Bible for themselves in their own everyday language, and draw their own conclusions from it—which Bible, by the way, is now available in 2,370 different vernacular languages.

It's a shame that McGrath never drills down to explore in depth the chaos and creativity of Protestantism's "mutating" (p. 461) impulse. But in all fairness, he's a victim of his subject matter. Having decided to cover five hundred years in five hundred pages aimed at a general readership, to let as many diverse perspectives have their fifteen seconds of fame, and to show how Protestants disagree on almost everything, perhaps it was inevitable that his book would only glide across the surface. McGrath is also a victim of his own Christian preferences. No historian is neutral, but there's an apologetic agenda just beneath the surface of his exposition. He mentions not only the good but the bad and the ugly of Protestantism, but instead of letting the historical chips fall where they might he works hard to rehabilitate his subject (especially its Reformed wing).

One could nitpick at unexplained references that will stump his intended readership (eg, the "Gunpowder Plot"), or omissions and oversights, but this is still an accessible introduction by a remarkable scholar to the "uncontrollable" (pp. 2, 463) forces that were unleashed 500 years ago by Martin Luther and his kin. I'd love to see a more scholarly treatment by McGrath that explores in depth what he rightly describes as the most fundamental question of any religion: who has the right or authority to define its faith (cf. pp. 3, 209)? The answer to that question seems to be "no one," for "what [has] distinguished Protestantism. . . is its principled refusal to allow any authority above scripture" (p. 221). In the end, then, Protestantism is "a method" and "not any one specific historical outcome of the application of that method" (p. 465).