Book Notes

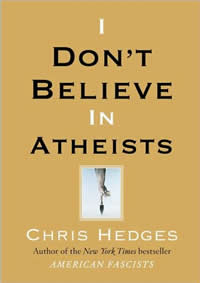

Chris Hedges, I Don't Believe in Atheists (New York: Free Press, 2008), 212pp.

Chris Hedges, I Don't Believe in Atheists (New York: Free Press, 2008), 212pp.

Chris Hedges grew up as a pastor's kid in rural upstate New York, where his father was a Presbyterian pastor. Six days after graduating from Colgate University he began a two year stint as a pastor in the violent ghetto of Roxbury in metro Boston, an experience so unsettling that he left the church and seminary. After a year in South America he completed his degree at Harvard Divinity School, though not without caustic opinions about his liberal professors who romanticized the poor whom they had never met, and the lectures which he experienced as "intellectual shell games." Then, for twenty years, he covered a dozen wars in Central America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans.

These life experiences deeply inform Hedges's writing. He's been around the block and he does not suffer armchair pundits easily, which is about the nicest description he might use about the so-called new atheists like Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Chris Hitchens, and Daniel Dennett. This book originated with his separate debates with Harris and Hitchens at UCLA in May of 2007. These atheists, says Hedges, are the reverse image of fundamentalist Christians. He derides them as "carnival barkers" whose stock in trade includes gross intolerance for any "other" who is different from them, facile analysis, the abuse of evolutionary biology as a "surrogate religion," the confusion of scientific progress with moral progress, racist and crude generalizations (especially about Muslims), and a "staggering historical and cultural illiteracy." But that's not the bad part.

What really angers Hedges about the new atheists is their uncritical belief in the utopia promised by the Enlightenment thanks to the inevitable progress of science and the innate goodness and rationality of humanity. He's outraged at their evangelistic effort to remake the world in the image of an ostensibly "enlightened" west. He quotes Harris and Hitchens who recommend slaughtering unwilling converts. Which proves his point, that "reigns of terror are the bastard children of the Enlightenment." Muslims have a long way to go before they catch up with the tens of millions of people, mainly civilians, slaughtered by the Nazis, the Soviets, and the Chinese (149).

Drawing upon heavy doses of Nietzsche, Freud, Dostoyevsky, Reinhold Niebuhr, Samuel Beckett, and Joseph Conrad, Hedges urges us to recover our sense of the fallenness of humanity. We must repudiate our smug and self-congratulatory self-image as morally pure purveyors of enlightenment, for "to turn away from God is harmless." But "to turn away from sin," which is what the new atheists do, "is catastrophic." Divine intervention in the world, he suggests, is "absurd" (13), history appears "purposeless" (42), and human nature remains "irredeemable" (67, 151). Rejecting absolutisms of all kinds, we must embrace our limitations and imperfections. The utopian dreamers, "lifting up impossible ideals, plunge us into depravity and violence." Only in such brokenness and humility can we see "the limits of reason and the possibilities of religion" (185).