Book Notes

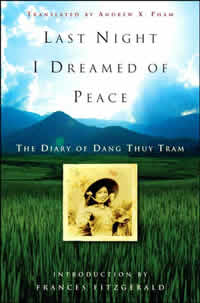

Dang Thuy Tram, Last Night I Dreamed of Peace; The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram. Translated by Andrew X. Pham, Introduction by Frances FitzGerald (New York: Harmony Books, 2007), 225pp.

Dang Thuy Tram, Last Night I Dreamed of Peace; The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram. Translated by Andrew X. Pham, Introduction by Frances FitzGerald (New York: Harmony Books, 2007), 225pp.

"Last night I dreamed that Peace was established," Dang Thuy Tram confided to her diary. "Oh, the dream of Peace and Independence has burned in the hearts of thirty million people for so long. For Peace and Independence, we have sacrificed everything. So many people have volunteered to sacrifice their whole lives for these two words: Independence and Liberty. I, too, have sacrificed my life for that grandiose fulfillment." Thuy never saw the fulfillment of her dream. She was only twenty-seven when on June 22, 1970 American soldiers put a bullet through her forehead.

Dang Thuy Tram (b. November 26, 1942) was a surgeon fresh out of medical school who headed a field hospital in the remote, mountain jungles of Vietnam. She operated without anesthesia, rebuilt her clinic every time it was bombed, tended to the peasants whose villages had been burned and bull-dozed, hid in her underground shelter, and suffered the atrocities of war — kids stepping on land mines, helicopter gunships in the middle of the night, forests stained yellow by toxic defoliants, napalm bombs, amputees, and patients like Khanh, a twenty-year old victim of a phosphorous bomb whose charred body, burned to a crisp, still smoldered with smoke an hour after it was admitted to her clinic.

The sparse possessions found with Thuy's body included some medicines, a rice ledger, a Sony radio, and this diary. When the American soldier Fred Whitehurst found the diary during the mop-up, he violated military regulations, kept the diary, and took it home with him in 1972 after three tours of duty in Vietnam. In April 2005 he was able to deliver the diary to Thuy's eighty-one-year old mother and three sisters, who published it in Hanoi on July 18, 2005. In the following eighteen months Thuy's diary sold 430,000 copies — in a country where two-thirds of the citizens were born after the war ended and where books rarely sell more than 5,000 copies.

Much like Clint Eastwood's film Letters from Iwo Jima, Thuy's diary tells the story of Vietnam from the perspective of our "enemy." She's a fervent patriot devoted to Vietnam's revolutionary resistance. She longs for acceptance with the Communist Party which suspects her admitted bourgeois background and attitudes (her father was a surgeon and her mother a university lecturer). She rages with hatred against the American invaders, those "imperialist killers, vicious dogs, bloodthirsty devils, and terrible, cruel people who want to use our blood to water their tree of gold." More importantly, Thuy's diary reveals the longings of a fellow human being who misses her mom and dad and aches with loneliness for her boyfriend. FitzGerald's introduction, numerous footnotes that explain historical details, and two dozen family photographs complement Thuy's deeply human dream of peace.