Book Notes

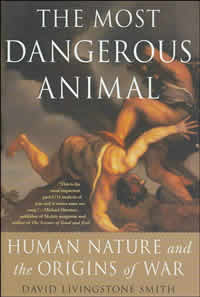

David Livingstone Smith, The Most Dangerous Animal; Human Nature and the Origins of War (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2007), 263pp.

David Livingstone Smith, The Most Dangerous Animal; Human Nature and the Origins of War (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2007), 263pp.

In the last century alone over 200 million people, mainly civilians, have been slaughtered in war by their fellow creatures. It's mind boggling to imagine what that number would be if we could calculate the figure beginning with antiquity. In this book written for a broad readership, philosopher David Livingstone speculates about the "big question" of war. Why do humans kill each other on such a mass scale and with such ferocious cruelty? How and why do we ignore or overcome our deepest inhibitions about taking another's life? Livingstone frames the question as a choice between two broad alternatives. He rejects the idea that war is a matter of nurture, a learned behavior, or mere "cultural artifact." Rather, he argues that war is deeply embedded in human nature, that it's innate and, if you will, our natural impulse. As such, war is not so much a pathology or aberrant choice, it's "a normal feature of human life."

To make this point Livingstone appeals to science. Much of his book is not about war at all but about neurobiology, Freudian psychology, evolutionary biology, anthropology, history and archaeology. He's a strict materialist who rejects the notion that there is any "credible alternative to a materialistic conception of mind" (96). As for ethics, "the idea that moral values are objective simply does not hold water" (132). He's convinced that "our taste for killing was bred into us over millions of years by natural and sexual selection" (161) and a "hideously cruel" evolutionary process. That being the case, war might be tragic and regrettable, but in my mind Livingstone has a hard time transcending the conclusion of Arthur Schopenhauer who described nature as a "scene of tormented and agonized beings, who only continue to exist by devouring each other, in which, therefore, every ravenous beast is the living grave of thousands of others, and its self-maintenance is a chain of painful deaths" (67). Life without transcendence is difficult.