Book Notes

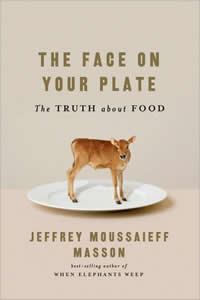

Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, The Face on Your Plate; The Truth About Food (New York: WW Norton, 2009).

Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, The Face on Your Plate; The Truth About Food (New York: WW Norton, 2009).

Reviewed by Chad Abbott in the Englewood Review of Books (May 8, 2009):

From the opening introduction and headlining title, author Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson demonstrates, in his new book The Face on Your Plate: The Truth about Food, a way of eating with compassion. This text focuses on the origins and many faces behind the foods we consume and is both timely and insightful. Building upon the tradition of Micahel Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and taking cues from his recent psychological research into the life of elephants in When Elephants Weep, we are challenged to begin “letting go of everything [we] have always believed or understood for a leap into the unknown.” Comparing it to the way some come into religious conversion, Masson suggests that the most logical answer to the suffering of animals and a more sustainable future to our food consumption is to take up a life of ahimsa, or non-violence, which for him ends in adopting a vegan lifestyle.

One of the unique factors of this text that sets it apart from similar books is that Masson comes to this task not only as a proponent of the food revolution, but also as a psychoanalyst. He sets the tone in his introduction for the rest of the book by suggesting that at the heart of consuming our meals everyday is the capacity for participating in violence or participating in compassion or empathy. He speaks of his own journey and those of others who have made similar choices and compares them to much of what our culture teaches about the realities of animals and our food. In the end, he sets out in this work to make the argument that killing animals for human consumption contributes to violence and does not take into account the enormous effect of suffering, not just on the animals themselves, but upon our environment and our human health. Masson breaks the remainder of his book into five chapters, beginning with the world in which we live. He suggests that this is the only world that we have to live in and that our production of meat through factory farms and mass producing of cows and pigs and chickens is threatening our existence. Chapters two and three focus specifically on the treatment of animals and fish in the slaughtering process. Much of what Masson draws upon in these chapters can easily be found in other texts; however, he has added some very unique elements of psychoanalysis into the suffering of animals and how it relates to the psyche of human beings. He suggests that if most of us knew the horrors that animals go through we would reconsider eating meat and fish. In fact, Masson suggests that the meat and dairy industries are smart in that they seek to distance the consumer from the actual slaughter of animals in hopes that this will keep people believing that it is humane to kill animals for consumption. This factor of hiding the face that is on our plates actually leads to the most fascinating topic of this book: denial, the subject of Masson’s fourth chapter. The Hippocratic oath to “do no harm” fills his final chapter, as he demonstrates a day in the life of a vegan and the variety of ways that a person can adopt such a life.

I am convinced that this text is worth reading and offers tremendous insight into our own psyche and to the psychology of our food choices. In fact, the field of food ethics and the food revolution has been so expansive in the last five years that another book conveying similar information is not truly needed. The Face on Your Plate, however, is not one of those books. While there are many things that Masson draws upon that could be considered a repeat of the literature, a good bulk of the book provides sound research into the psychological reasons for adopting a vegan diet. Above anything, the heart of this writer is to call each of us to a way of ahimsa, non-violence and compassion. In my opinion, any greater call toward non-violence, love and compassion ought to be worth our consideration. Whether one ever becomes a vegan or not is almost secondary to the call of a compassionate life and while Masson argues that we ought to become vegan or vegetarian, it is clear that his largest hope is that we will all have more empathy and that greater empathy will on some level lead to less suffering in the lives of animals. Vegan or not, may we all think more compassionately upon the food we eat, the face on our plates, and seek a life of empathy.