Book Notes

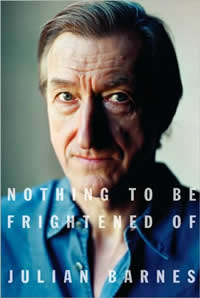

Julian Barnes, Nothing to Be Frightened Of (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 244pp.

Julian Barnes, Nothing to Be Frightened Of (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 244pp.

Novelist Julian Barnes (b. 1946) was never baptized and has never attended a church service in his life, and so he's never had any faith to lose. He came by this unbelief honestly; his father was an agnostic and his mother said that she didn't want "any of that [religious] mumbo jumbo." But the certainty of total extinction, both personal and cosmic, and the terror which absolute annihilation provokes in him, causes Barnes to admit in the first sentence of his book that while he doesn't believe in God, he misses Him.

The title for his disquisition on death comes from one of his journal entries over twenty years ago: "People say of death, 'There's nothing to be frightened of.' They say it quickly, casually. Now let's say it again, slowly, with re-emphasis. 'There's NOTHING to be frightened of.' Jules Renard: 'The word that is most true, most exact, most filled with meaning, is nothing.'" Exactly where the emphasis on nothingness rightly falls is what occupies Barnes' considerable talents. The result is a book characterized by deeply personal candor and broad-ranging critical inquiry that encompasses art, music, philosophy, science, literature, and family memories.

The Christian story claims that Jesus "conquered death and brought life and immortality to light through the Gospel" (2 Timothy 2:10). This story succeeded, says Barnes, not because people were gullible, because it was violently imposed by throne and altar, because it was a means of social control, or because there were no other alternatives. No, the Christian story succeeded because it was a "beautiful lie" (53) or "supreme fiction" (58). It's the stuff of a great novel, "a tragedy with a happy ending." And good novelists, says Barnes, tell the truth with lies and tell lies with the truth. There's always a "haunting hypothetical" for Barnes: what if this Grand Story is true?

The strictly secular-materialist option is simple enough. When your heart and brain cease to function, your self ceases to exist. But in this view the "self" is nothing more than random neural events. There's no ghost in the machine to begin with, so in fact there's no "self" that ceases to exist. In post-modern parlance, personal identity is a social construction. But Barnes has nagging suspicions about this neat and clean scientific scenario. Even if they are hard to define or describe, a common sense outlook, endorsed by the vast majority of humanity that has ever lived, is that intelligence, aesthetic imagination, our moral impulse, consciousness, love, gratitude, guilt, regret, and the longing for immortality — all of these seem to point beyond themselves. They have the ring of truth that makes them hard to define by mere biology.

And so Barnes wonders, given his genuine lack of religious faiith, is it proper to seek and to assign any meaning to his personal story? Does his life enjoy a genuine narrative? Or is it only a random sequence of events that ends with total extinction, such that any and all meaning-making is pure "confabulation?" One thing you can be sure of, Barnes reminds us — in the end, it doesn't matter what you think. The divine reality, or lack thereof, is what it is, and so "the notion of redefining the deity into something that works for you is grotesque." There's a deep irony here. In his review of The God Delusion by the Oxford atheist Richard Dawkins, Jim Holt observes that if "the after-death options are either a beatific vision (God) or oblivion (no God), then it is poignant to think that believers will never discover that they are wrong, whereas Dawkins and fellow atheists will never discover that they are right" (New York Times, October 22, 2006).